Leroy "Lee" R. Johnson

Service Company

It all started on 10 October 1919! I was born in

Detroit, Michigan and I’m still wondering where the time went. When the Great

Depression hit, I was 10 years old and I remember how devastating it was for

everyone, especially the kids. Most kids had nothing and that meant very little

food. We survived because my Dad was a resourceful man. He was in the import and

sales business – an early entrepreneur you might say. He imported a form of

liquid from Canada and sold it in Detroit. Later in his career, he owned a bar

in Detroit and we managed to survive the Depression. I attended an elementary

school in Detroit and in high school I played foot ball. I wasn’t the biggest

kid on the team, but I learned how to take and give some pretty solid hits.

After high school (1939-1940) I worked for Detroit-Toledo Ironton Railroad. I

worked in the Ford Admin building where I checked railroad car way bills, train

routes, and which cars made up which trains. My draft number came up when I was

21, and my railroad career quickly ended. My actual induction date is 19 June

1941 – just 6 months before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

I reported to Camp Grant, Illinois which was the reception station and I was

there for just 24 hours. From there I went to Camp Wolters, Texas for 13 weeks

of training on operation, maintenance and care of heavy weapons. In those days,

heavy weapons were the 81mm mortar, the .50 Cal machine gun, and the .30 Cal

water cooled machine gun.

After Camp Wolters, I was assigned to D Company, 1st Infantry Regiment, 6th

Division at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri. There we trained and it seems like we

were on maneuvers all the time. In hindsight that was good for all of us

Privates because a couple of years later, we got to put that training to good

use in France, Belgium and Germany.

Some of our training was in the Mojave Desert and again, it seemed like we were

on maneuvers day and night. I left Camp San Luis Obispo in March 1943 and

reported to Fort Benning for jump school and rigger training. Jump school wasn’t

easy, but at age 23 and just having been through very tough Infantry training, I

completed the Airborne training; made my 5 jumps and proudly wore my parachutist

wings.

After rigger school, I was sent to Camp Mackall, North Carolina and was assigned

to the 517th Parachute Infantry Regimental Combat Team. The 517th was part of

the 17th Airborne Division and it consisted of the 460th Parachute Field

Artillery Battalion and the 596th Parachute Combat Engineer Company. Again

we trained continually but this time we were training in terrain that more

resembled Western Europe. There was no doubt where the 517th was going to be

deployed.

In May 1943, we received orders to report to the steamship Santa Rosa at Camp

Patrick Henry which was near Newport News, VA. The Santa Rosa was an ocean liner

belonging to the Cunard Ship Line – not a bad way to cross the Atlantic except

all of knew we had to get past the German U Boats. Other passengers on the Santa

Rosa were 300 WACS and some Air Force officers. One Lieutenant thought he would

go visit the WACS, but a very stubborn Army sergeant firmly informed him that

wouldn’t be possible.

We arrived in Naples, Italy and awaited orders for combat. We waited for about

10 days because our heavy equipment was on other ships and we had to wait for it

to arrive. After getting our heavy equipment, we were assigned to combat north

of Rome. At Camp Mackall, I was promoted to T5, and once we got to Italy, I was

promoted to T4. Captain Freud put me in the rigger section and assigned me to in

charge of distributing rations. I got to know the roads pretty well in that part

of Italy. Soon after that, eighteen of us riggers learned about the plans for an

upcoming jump and we volunteered to participate on the jump scheduled for 15

August 1944.

As we were preparing for the jump, Colonel Graves was supposed to report to the

7th Army Provost Marshall to explain why we had so many excess vehicles in the

517th. I’m not saying we “midnight requisitioned” vehicles but somehow they just

mysteriously appeared in our motor pool. Luckily for Colonel Graves, the meeting

with the Provost Marshall was scheduled for 15 August and Colonel Graves was too

busy that day to meet with the PM.

In preparation for the jump, we assembled north of Rome where there were many

small dirt airstrips. It was so dry that the dust from the first airplanes

obscured the runways and some of the pilots had to use their compasses to stay

lined up with the runways for take off. Somehow we were in the air and there

were no aircraft accidents. I remember that we were well prepared for this

assault. Most of us carried the M-1 which was broken down into 2 pieces and

carried in the weapon’s container. We also had 2 bandoleers of ammo, a cartridge

belt and hand grenades. We were entering combat that morning as light

infantrymen. We took off at about 10:30 or 11:00 pm and I was on the last plane

which was the 3rd Battalion serial.

We jumped at about 4:30 in the morning and because of the heavy air with

overcast, I had a soft landing. I was 9th or 10th man out the door and I think

the jump altitude was about 600 feet. Some of the planes took ground fire, but

none were shot down. I landed between 4 small fruit trees and immediately

assembled my M-1. At daybreak, several of us located a sign that telling us we

were 32km from Le Muy so we knew where we were. Later that day, there was a

firefight with a German unit and 22 of them surrendered. We turned these

prisoners over to the Free French in the area and we never heard anything about

them again. We didn’t have any casualties from this fire fight, but they did.

One of their officers pulled out a map and told us we weren’t supposed to be

there – he said we were supposed to be in Le Muy.

As we were getting ready to move to LeMuy, there were 4 Second Lieutenants who

were arguing about who had date of rank seniority. An OSS Major and a Master

Sergeant came out of the woods and the Major told the lieutenants he didn’t care

who had date of rank – just to get these men on the road to Le Muy where they

were supposed to be. That settled that argument.

That troop movement to Le Muy consisted of 3rd Battalion Headquarters and I

Company soldiers along with 30 or 40 Brits and the 18 riggers. The Brits were

the rear guard and they noticed that some German trucks started following us.

Along the road, we passed a huge rock that was about 20 feet high and one of the

Brits climbed up the rock and dropped a land mine or some other explosive on the

lead truck. The other 2 trucks retreated towards Draguignan and that was the

last we saw of the German trucks.

We proceeded towards Le Muy and on D+2 we started receiving aerial delivery of

rations and supplies. The planes dropped the bundles very close to our target

panels but they were scattered around a farmer’s field. I hitched a horse to a

cart and went around picking up the bundles while others posted security. The

horse was about 18 hands tall and farmer was yelling at us because he thought we

were stealing his horse. I had to stand on a ladder to get the harness on that

horse. When we finished picking up the bundles, we returned the horse and cart

to the farmer. He was very thankful and he gave us two bottles of wine.

In September when the line troops were in the mountains, Service Company sent me

to the message center and I was detailed to distribute messages. Another soldier

and I were message couriers and we worked 24 hours on, and 24 hours off. That’s

how I got to Nice and I enjoyed my 24 hours off duty several times.

Most of my courier driving was in the mountains where the roads were narrow and

there were steep drop offs – it got a little scary when I had to drive close to

the edge of the road because the road could easily give-way. In Detroit, there

were no narrow hair-pin mountain roads to learn to drive on so I had to learn

this under fire. Most of the roads had been bombed, mined or there were craters

at every turn. Because of the damage to the narrow twisting roads, some trucks

weren’t able to pass easily. I learned later that the 596th Parachute Engineer

Company repaired some of these roads which allowed vehicles to pass safely.

I always had a runner with me and he carried the classified paperwork. We both

had our M-1’s and he looked out for me, and I looked out for him when the German

artillery came close. Both of us spent time diving in the ditches and waiting

for the artillery and mortar attacks to end. Neither of us had any combat

injuries and we managed to dodge the incoming fire. At this time, my unit

(Service Company) was positioned at the base of the Maritime Alps near the

village of L’Eescarene (Luceram?) and my runner and I spent a lot of time on the

mountain roads delivering messages and grabbing sleep and meals when we could.

We were supposed to be 24 on and 24 off, but that didn’t always happen. Many

times I slept in the driver’s seat of my jeep and that’s mainly because I didn’t

want my jeep stolen.... excuse me, “borrowed.”

We were relieved just after Thanksgiving Day following 94 continuous days in

combat. We also received 500 replacements along with orders to move North. It

was on 1 December 1944, that the 517th was assigned to the XVIII Airborne Corps

(ABC) and directed to move to Soissons. The 1st Special Services forces was

disbanded with this reassignment to the XVIII ABC. I drove my jeep up the Rhone

Valley but most of the unit were transported on a train. Those guys didn’t see

the damaged and destroyed bridges compliments of the Army Air Corps because they

were riding in what we’d call cattle cars. Along the road were hundreds of

damaged German vehicles damaged by Allied bombs and strafing. These vehicles

were just pushed to the side or off of the road allowing us to pass.

It was kind of funny to see what happened at train stops. The French railroad

workers had to change crews from time to time, and that was the only time the

trains stopped. There were no latrines on the cattle cars so when the trains

stopped, it was a mad rush to find a latrine or a suitable place to call a

latrine. The train would start moving again without notice, and the GI’s would

have to scramble (run) to catch the train. I think they all made it.

On 4 December we were located in Menton which is north of Nice and Cannes. At

that time, these towns weren’t vacation resorts and it was cold, wet, and

essentially a miserable place to be. Some paratroopers managed to find local

“company” but that was short lived. The reality of war wasn’t far from our

thoughts. We knew we’d get orders to move north most likely into Belgium and

later into Germany. Sure enough, on 17 December we received orders to move to

Belgium starting on 22 December. The weather could not have been worse – we were

in riding open cattle cars in the cold, sleet, freezing rain and we were all

soaked.

We stopped in Namur, Belgium so the commanders could receive assignment orders.

The 1st Battalion was attached to the 3rd Armored Division in the Soy-Hotton

area of operations and we spend 22, 23, and 24 December working with the 3rd

Armored Division. It was here that the actions of the 1st Battalion, 517th PRCT

warranted the award of the Presidential Unit Citation. It also was the location

of the heroic actions of PFC Melvin E. Biddle who during the battle of Soy-Hotton

that earned him the Medal of Honor. PFC Biddle’s Medal of Honor citation is

available at the Mail Call site.

After Soy-Hotton, we moved on to the Bulge. Somewhere along a forgotten Belgium

road I lost my jeep – actually, my jeep was a casualty of German artillery fire,

but my runner and I had jumped into a deep ditch and again, we dodged a big

bullet. We did a lot of driving at that time since the roads were too wet and

muddy for motorcycle couriers. My runner from the Engineer Company (sorry I

can’t recall his name) and I were asked if we wanted relief, but we both

declined. It was much more exciting to be on the road than in a foxhole.

Somewhere along the way, we came across a destroyed tank. I looked inside and

found a pair of tanker pants that came in handy and another handy item I found

was a Thompson sub-machine gun which I carried along with my .45 and M-1.

There was a lot of stationary fighting near St Vith and Manhay. By that I mean

neither side gained ground for any length of time – kind of a stalemate. My

runner and I had several close scrapes but we got out of them OK. Every day we

were doing something new – there was very little “down time.” We were either

delivering messages or transporting wounded from aid stations to hospitals. It

was miserably cold, and some guys had to urinate on the trigger group to get

their M-1 to fire. When we did get a break, all I wanted to do was sleep.

Once we moved into Germany, we located our CP near the villages of Schmidt and

Bergstein. This area is recorded as being the heaviest mined of any German

defensive position. It took a long time for safe passages to be located and that

was the job of the 7th and 596th Engineers. Unfortunately, the Germans were

watching the mine clearing operations and they made those cleared lanes “targets

of opportunity.” We lost a lot of troops in this area. The Regiment saw some of

the worst fighting that war can present. At one place there was a big swamp – it

was a terrible situation. General Gavin said he’d never seen anything as bad.

There were cadavers everywhere – some our boys, mostly theirs. When we attacked,

we shot artillery into the villages where the Germans were and when we occupied

the villages the Germans shelled us in the same villages. There was nothing left

standing in most villages that we saw. Fortunately, the civilians had all

evacuated the villages and no more casualties resulted from the shelling.

We pulled out of that area on 13 August and we were no longer in the 517th. I

was assigned to parachute maintenance with the Maintenance Company of the 13th

Airborne. When the point system was announced I had 84 points, but you needed 85

points to go home. With 84 points, I was sent to the 101st Airborne Division.

Later after I received paperwork for the Bronze Star, my points went to 92. The

Bronze Star was issued by the 517th, but somehow it was delayed by the 13th, and

I finally received it on 25 November 1945 at Camp Attabury.

Throughout the campaigns – Italy, France, Belgium and Germany, I was always

assigned to Service Company along with the other riggers. We were a small outfit

and we were all good friends. I remember Marvin Winston who was also from

Detroit. He called me Uncle and that’s probably because I was 24 years old and

older than most GI’s. Ed Inman also was a good friend – he was from Westland,

Michigan. John Gogoleski was 18 years old and he was from someplace near

Detroit. There were lots of GI’s from Michigan and a few from California. Most

were about 18 years old – just kids but they grew up fast and they did what

needed to be done.

After serving 4 years, 5 months, 23 days, and 55 minutes, I was discharged and I

returned to Detroit. After my Army service I went to work for Borg-Warmer in

Sterling Heights, Illinois. Later after retiring, I lived for a while in Las

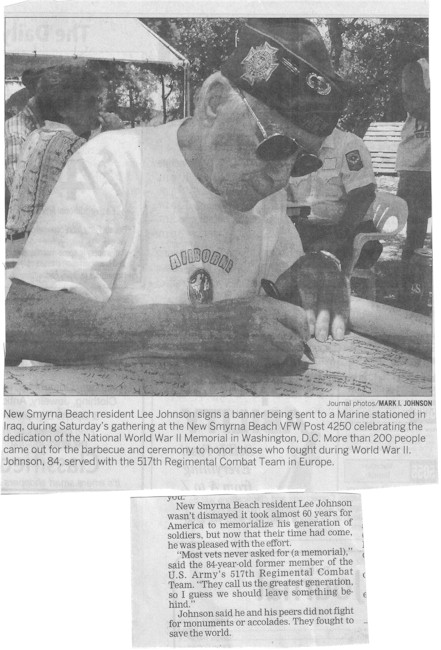

Vegas. My wife Doreen and I now live in New Smyrna Beach, Florida where I can

hang out with other Veterans for coffee in the mornings and I can attend the

reunions in Kissimmee . I have attended numerous 517th Reunions, and I hope to

attend many more. My sincere thanks to all those who work so hard to make these

reunions possible.

Received from Lee Johnson via Col. Earl Tingle

April 2013