|

A Devil in Baggy Pants -or- "What Did You Do In the War, Daddy?" by Eugene L. Brissey |

|

On March 23, 1943, the United States had been at war approximately fifteen months. This fact is not of particular significance, but the fact that I was 18 years old on that date was of great significance to me. I was not old enough to vote; I didn't know I was allowed to protest the war, instigate riots and participate in other such excitement, but I knew I was old enough to go into the service. So, like the typical all-American-boy, I registered for the draft.

I could have avoided being drafted by joining the Navy, or joining anything else for that matter. However, I decided to wait for the draft. One thing for sure I did not want to go into the Navy. Didn't like those stupid-looking bell-bottom Navy uniforms.

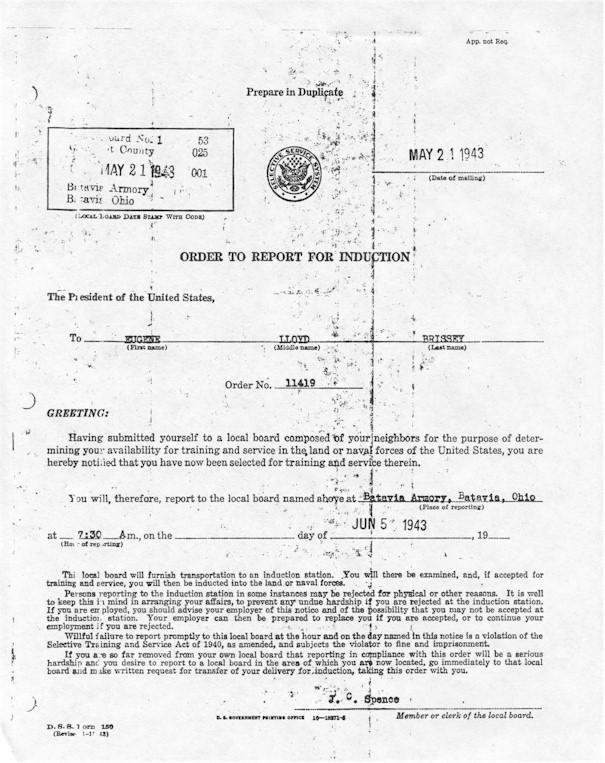

Not many weeks passed before I received a letter inviting me to come join the troops. That letter follows this introduction and started me on the way to the 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment. The road to the Troopers was not exactly straight; in fact, I almost landed in the Navy.

When I was called for induction into the service, the men at the Induction Center looked me over and decided that I was a good Sailor prospect. I heard them say Navy and saw the man raise a big Navy stamp to stamp Navy on my papers. Although I knew that they thought they were doing me a favor, I said, "No! Please don't put me in the Navy." Those guys looked at me as though I had two heads (both empty) and went into a conference. Soon they had reached a decision and mumbled something about me just being 18 a little while, so I could have my wish -- the Army. They no doubt decided that anyone dumb enough to prefer the Army over the Navy would probably fall overboard and drown anyway.

There I was, 227 feet (more or less) above sea level with both feet on the ground, with only a few buttons to unbutton, and had never heard of a parachute -- especially one that wouldn't open. For me, they all opened and became, along with my jump boots and jump suit and many other things, fond memories of a great experience. Others, too, have memories, or at least had knowledge of the United States Paratroopers of World War Two. It is well known that Hitler knew we were there, and reports indicate that he called us, "Those Devils in Baggy Pants."

Now, many years later, I'm writing a few of the highlights of my adventures in the Paratroopers. What I write here is for my three wonderful daughters, Denise, Lisa and Gisele. Though I have only covered about ten percent of the thrills, miseries, and other aspects of my 28-month military career, you darling girls will have part of the answer, should you ever ask, "What did you do in the war, Daddy?"

Dressed in the last set of civilian clothes that I would be wearing for a long time. I joined the group aboard the bus for Fort Thomas, Kentucky. Fort Thomas was the reception center where all local recruits were given their first taste of Army life. I didn't exactly join the group -- we were all more or less shoved in like a bunch of Army mules. We didn't mind too much, after all we were chosen by our friends and neighbors, so we had to show them that we appreciated their kindness, intelligence, and ability to select the best.

As the bus rolled into Fort Thomas, I began to have doubts about Army life. One of the first things that caught my overawed eyes was a group of soldiers picking up paper and any other objects which were not a part of the scenery. This was not so bad really, but those guys with the guns, who were guarding the poor souls, looked mean to me. For some reason, at that moment, I thought that I would probably wind up in front of those guns.

We were soon herded into a large building with long rows of bunks, or beds, with metal springs but nothing more. I knew the Army was tough, but it didn't seem right that tender young guys like us should have to sleep like this. Soon a mean-looking General or something like that came in. We knew he was a big shot because he was so mean and had a stripe on his shirt sleeve. Was I ever impressed with such attention so soon. This big shot told us to get the "heck" out to the store house and grab a mattress and other bedding. Can you imagine ... no room service. Must have been the maid's day off, I thought. I found out later that they must have fired all the maids because they never came back.

After we dragged in our bedding, old big shot "one stripe" wanted to play games. He wanted to see how fast we could make those bunks, and the last guy finished could wash dishes for a week. I never did like to wash dishes, so I immediately became the fastest bunk maker in the Army. Old "one stripe" was impressed. I slept in peace.

The next day we became real soldiers. We were issued uniforms. Real honest-to-goodness GI clothes. Now it so happens that in those days that I was a little type guy weighing in at 128 pounds. But I sure fooled those boys who were giving out the uniforms. They gave me everything king-size, and I sure felt like a king in those clothes until I looked in the mirror and then I wondered if those Navy bell bottoms were all that bad after all.

There I stood, a future General or something, and I didn't look good at all. I thought for a moment that I had put the barracks bag on instead of the shirt, but that looked good compared with the pants. But the thing that really impressed me were those shoes ... they were big. Now those shoes which they gave us they said were very fine, I asked for size seven but they gave me size nine. Like I said, I sure fooled those guys.

After my first week at Camp, the General gave me a pass since he didn't need me. So I decided to go home. I sneaked around back alleys so that no one would see me in that uniform but as luck would have it I ran into a bunch of teenage girls. They started to whistle. I thought they were calling their dog, so I looked around to see if by chance I had frightened their dog, but there was no dog. Those sweet things were actually whistling at me. I smiled and walked out into the open and grew into those pants just a little bit more and those shoes felt smaller too.

The folks at home were impressed and wanted to know what I was going to be in the Army. I told them I didn't know since they already had a General who held bunk-making contests.

When I got back to Fort Thomas the clerk who was running the Army also wanted to know what I was interested in doing. I told him that I didn't know, but I didn't want to be in the Navy. He thought that was real funny. I could tell he thought it was funny by the way he clenched his fist to keep from laughing. He asked me if I would like to be a Paratrooper. That sounded pretty good so I said yes. Before I could change my mind he gave me a statement to sign. It read as follows:

VOLUNTARY DUTY IN PARACHUTE UNITS

I, Eugene L. Brissey, hereby volunteer for duty with parachute troops. I understand fully that in performance of such duties, I will be required to jump from an airplane and land via parachute.

SIGNED:

DATE: June 21,1943

I had given up my chance to be a General and joined the greatest, most daring, the toughest outfit in the service. The folks at home thought I had lost my mind for sure. My best girl, Edith Moore, must have given some thought to trading me in on some Four "F" type.

I managed to keep off KP while at Fort Thomas but did learn to pick up cigarette butts, paper and a few other objects. I also found out that the big shot with one stripe was just a Private First Class which is next to nothing unless you are a Private Last Class as were all of us who learned to build a bed out of an arm load of bedding and a bunk with springs. Actually, that bed was very comfortable.

Army food wasn't too good in the beginning. The rolls that they gave us they said were very fine, but one rolled off the table and wounded a friend of mine. And the coffee that they gave us they said was very fine, it was good for cuts and bruises and tasted like iodine.

In late June 1943 I visited home for one last time before being shipped south for the real thing, basic training with the wild and rough paratroopers. One of the last things I remember of this last visit was Ole Edie putting on my oversize shoes and doing a dance. Man was that funny ... like an average size man with his feet poked into two Volkswagens.

June 1943 was nearing the end when the selected few departed Fort Thomas for the deep South and a try at being paratroopers. I was one of 21 who thought that being a paratrooper was the best way to do our bit for the war effort. I must say that at that time most of us had very little knowledge of what the Army was like and even less of what war was like. Still, we felt rather important in our oversize uniforms, most away from home for the first time and for me at least it was my first memory of being on a train.

On a bleak afternoon a couple of days later we arrived at Camp Toccoa deep in the red mud of Georgia. It was easy to see why Sherman, or was it Sheridan, went through Georgia so fast, there was nothing worth stopping for. But, we stopped and climbed from the train with our only possessions in our barracks bags. It was here that I received my first real taste of Army methods. From up front somewhere someone called my name; I said "here" and some other clown screamed at me as though I had stepped in his mess kit, "When your name is called you say 'Here, sir' and don't forget it." I didn't forget it because I still remembered those boys at Fort Thomas picking up paper with a gun in their back.

We rode in trucks through the dismal area of this Camp in the red mud and soon received our assignment to barracks. The barracks, our new home, were long rough buildings with a row of double bunks along both sides. The Camp seemed deserted, and we later learned that all the troops were on the rifle range firing their rifles. We had joined an outfit which had been in training for several weeks, and we were to be used as replacements for those who had not been able to make it with this tough outfit called Paratroopers. What chance did we have?

We soon found that our chance of staying with the paratroopers was very slim. During the next few days, we were given strict physical exams and a few other tests designed to eliminate a few boys who thought they were already in the outfit that wore the high boots. Several were eliminated early and sent to other parts of the service. I was told that I was too small since I weighed only 128 pounds. Of course I was shattered and asked for a chance. I told them that I had been going to a lot of parties and not getting much sleep just before I came into the service. They didn't seem to believe me but gave me another chance with what appeared to me to be just a delay. I am sure they thought I would not pass the other tests.

To me the next real test was jumping from high towers in a parachute harness and sliding to the ground in a big hurry. The guys ahead of me didn't do very well; they appeared to be afraid to jump from the tower and when they did they forgot to count or did something else wrong. When my turn came I could understand why. That was a frightening thing to do. The instructor put that harness on me and told me to jump out that door, make a half turn, count to three and keep my eyes open. It was now or never so, with all the courage I could muster, out I went. The next thing I knew I was on the ground looking into the face of a rough looking Lieutenant who said, "You did a fine job." I was now a member of the 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment, and so was one other of the 21 who made the trip to the land of the red mud.

The rest of that first week was very slow and easy with little or nothing to do. I know now that it was just a chance for a last rest until the end of World War Two.

Friday of my first week at Camp Toccoa was one I will never forget. The one thing that made it so was the return of the troops from the rifle range. These troops were dirty, tough-looking, big, and in my estimation well-trained. What a picture they made as they stood in formation, slapping those rifles around from one position to another on command from the officer in charge. Soon they were dismissed and charged the barracks with shouts of all kinds. It sounded to me as though they were charging a bunch of Indians in a cowboy picture. I watched them come into the barracks and wanted to stay out of their way, but they wanted to celebrate their return by telling of their feats on the range. I was even invited to listen.

The loudest loudmouth of them all was a short stubby guy from North Carolina. He was happy, to say the least, and I soon learned why; he had made the best score of all those from our bunch. This was my introduction to Clarence Billy Jones, better known as C. B. He took me under his wing and told all about his scores and showed me how to take the rifle apart and put it back together. This in itself seemed like an impossible task, but I soon learned that it was simple after a little practice. From this day C. B. was to play a large part in my military experiences.

At this time I thought I was well on my way to becoming a real fighting man. However, on Sunday morning my career had a setback. As I lay in my bunk, some rude character came up and informed me that I was supposed to be on K.P. I wondered how he figured that out, and he wanted to know why I hadn't read the bulletin board and found out for myself. What's this bulletin board kick I wanted to know, so he told me -- along with a few other things that wouldn't look good here. I didn't go on K.P. but instead received another thrill in my new career. I was about to resume my Sunday relaxation when some other spoilsport came in and told me that the Sergeant wanted to see me. Not everyone got such an invitation, I was sure, so I ran right in.

The Sergeant informed me that I was, as of now, Latrine Orderly. What, only here one week and already assigned to such a position. I'll admit that I didn't know exactly what to do, but I did know what a latrine was and no doubt that "orderly" was an important position of inspection or supervision. I walked proudly to the latrine and looked for someone to supervise but found the place empty. So, I inspected the joint and went back to bed. (I later learned that a Latrine Orderly is supposed to clean the place.)

As I lay there thinking of the fine title now bestowed upon me, I was further honored by a visit by a real live Lieutenant. He told me of another responsible job that needed attention. This time I was assigned to watch the store room, or did he say clean it up -- of course not, a Latrine Orderly should not clean a store room. I decided that I should watch the place, so with peace of mind I wrote eight letters. A nice Sunday even though I could not stay in bed.

As I look back, I wonder how I managed to live through that weekend without being placed on K.P. for a month.

The next two months were spent running, eating and sleeping, mostly running. This initial paratroop training was designed to make men of all who had the good fortune to keep up with the schedule. Many men fell but got up and ran some more. My main trouble was not physical; I ran before breakfast or any other time, but I couldn't keep in step. This was necessary so I would do everything I could to stay in the rear in hopes that no one would see me, but they always did and fussed at me until I was ready to quit. They didn't seem to understand that I was new in the outfit. One morning I got all the way in the rear of the column, but much to my dismay they turned us around and I found myself leading the whole company. This was very different, because I didn't see any heads jumping up and down and from that day forward I could keep in step.

My stay at Camp Toccoa was short, but definitely not sweet. It seemed that every effort was made to kill each of us. Now that I look back it is easy to see that all that tough training was very necessary to prepare us for the things to come. It was also obvious that the training had only begun.

In early August 1943 we were transported to Camp Mackall, North Carolina. I was surprised that we were not required to run all the way there; but as it turned out, we only walked the last few hundred yards. The change was really something, from red mud to the sand hills. This place had more sand than anything, in fact there was not much else other than pine trees.

One thing was about the same, our barracks. Two rows of double bunks inside a flimsy building that barely kept out the elements. In winter we warmed the place with two iron stoves. Actually, the camp was rather nice and cozy situated there among the tall pines and sand dunes.

Military training began in earnest at Camp Mackall, and we wondered when we would finally jump out of an airplane. Although we might have wondered, we had no time to worry about it because we were kept busy from daylight to dark, and sometimes after dark. First thing every morning we lined up for roll call and then ran for several miles. Then came breakfast and a full day of physical training and all types of combat training. Late in the afternoon we returned to Camp and left our guns and packs and then ran a few more miles. On these runs many men passed out from exhaustion but always managed to get up and run some more the next time. I had no trouble keeping up with all the rest and soon gained about 25 pounds of pure muscle. I was no longer a 128 pound little boy hoping to be allowed to stay in the paratroopers. The training was tough, but I liked it.

I soon had learned to fire the rifle as well as C.B., and I could take it apart and put it back together with my eyes closed. I was proud of the rifle and spent much of my brief spare time cleaning it. In fact, it seemed that we were cleaning our shoes, rifles or barracks during most of our spare time except Sunday which was a day of badly-needed rest.

Much of our training was with live bullets which made it seem just like war. One of the worst things was running along a narrow path, climbing fences, and going through creeks of filthy water while some nearsighted guy shot close to us with real bullets. I jumped in one of the creeks and went under water, man did that stuff taste bad. Some pour souls didn't quite make it, but no one got shot; some wished they had because the training was getting too rough. We had to crawl under bullets and barbed wire for about two hundred feet, and those bullets were pretty close to the ground.

I enjoyed throwing hand grenades more than crawling under bullets; in fact this was somewhat like playing baseball. We had to throw at targets at various distances with "dummy" grenades. This looked easy to me, so I said so. Unfortunately, our Sergeant (Sergeant Craig) did not appreciate my talking about how easy it would be to hit those targets. He bet me two dollars that I couldn't hit them all, so I bet him. After all, it would be worth two dollars to get him off my back. The Lieutenant came along arid this big-mouth Sergeant told him about the bet. The Lieutenant was a smart officer, so he wanted to win two dollars also.

Of course, I had to bet him too. I couldn't afford to lose four dollars, and I was worried about beating these superiors. Anyway, I started throwing grenades and hit the nearby targets without much trouble, but the worst was yet to come, and everyone was sure I couldn't hit the others. Everyone but me that was, so I threw those long ones right on the target. I won four dollars, and didn't make an enemy.

The training continued, and we became a little tougher each day, but Some of the big guys didn't seem to get the message. The very nice Sergeant, for one, thought he was really rough. He wanted me to wrestle him ... well, he was an old guy, about 25 years old, so I figured that anyone that old should be a little slow. We started a good-natured-type wrestling match, and by some chance every time he came at me I gave him a flip over my hip. He eventually shed a little blood, and decided that we had had enough. This suited me because I had a few bumps myself. This sort of thing was all in fun and a part of the training to make men of kids.

During late Summer in 1943, I received one of my biggest thrills in the Army. I was promoted to Private First Class ... a real live PFC. I was so proud that I sewed one stripe on my sleeve. Only one because this was all I had at the time, and I had found it lying around somewhere and had carried it around for several days. Not many days expired before I had one on each sleeve and fully realized that there were more important things in the Army than being general. As I recall, being a PFC meant five or ten dollars more each month, but it may have been only four bucks more. Anyway, it was worth it, and, after all, what could a young guy who was already receiving fifty dollars every month do with all that extra money. Being a PFC didn't give me any more work nor more responsibility, but it sure looked better than "Pvt" in the return address on my letters. Besides that, it gave me a good reason to try harder and not goof up. One goof and they could take away that stripe. That would be terrible or worse, so I didn't stray too far off course.

Food was always an item of extreme interest, and the mess hall was always a place to stay away from except at meal time. However, very few, if any, privates or privates first class managed to escape kitchen police (K.P.) duty. I did my share of potato peeling and pot washing. Even had the mess sergeant chase me once or twice to get me back to the kitchen. This K.P. stuff really wasn't bad, but it was degrading to a PFC ... and privates. There happened to be a rather uncouth mess sergeant in our mess hall who made a couple of enemies. One night when the mess sergeant and some of his poker-playing buddies were playing poker, one of those enemies approached the window with a rifle. He contemplated his target, the mess sergeant, and in his words told later, "I took careful aim and squeezed the trigger ... I knew I had him by the way he jumped." Life can be rough and long, but death is permanent.

The time had finally come for the 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment to become a real parachute outfit. We had already discovered that becoming a paratrooper meant much more than jumping from a tower or, for that matter, jumping from a plane. We had many weeks of very rough and tough training behind us when we arrived at Fort Benning, Georgia, in September 1943. But, we were not finished with pre-jump training yet. We spent two more weeks running, doing pushups, jumping from towers and going through dozens of other exercises designed to make us strong enough and smart enough to jump from a plane and land via parachute. One of the most interesting and sure as heck one of the most important phases of our training was learning to pack a parachute. Packing a parachute meant placing a rather large chute into a real small package in such a manner that it would open when we jumped from the plane. We were paired in teams of two since packing a chute is a two-man job when you know little or nothing about it. I managed to be paired with a fine young guy who was also more intelligent than the average bear ... I mean paratrooper. Really, most people thought bears and many other "dumb" animals were smarter than paratroopers. This was never proved however.

Well, back to parachute packing. This brighter-than-average trooper to be was Roger Bender from Bloomington, Indiana. He, too, was to play an important roll in my military career or at least he was to share many experiences with me and will never be forgotten. Roger and I worked well together and packed ten chutes that opened, five for him and five for me. Fortunately, we didn't pack any that didn't open although we were told not to worry about it because if one failed to open we could take it back and get another one.

Much of the training was difficult compared to packing chutes though not as interesting. One of the less interesting bits was trying to learn to guide the chute after we jumped and the chute had opened. We were hooked into a harness and had to swing out from a tower and maneuver ourselves back. Sometimes I did, other times I didn't. It was during this exercise that I learned another meaning of PFC. I was hanging out over thin air trying to get back on the tower when the instructor yelled, "Praying for Corporal, huh?" I wondered what he meant so he said, "You're a PFC and that's what all you PFC's are doing." I wondered if he thought my chances were slim while watching me dangle out there kicking like a mixed-up chicken.

The closest thing to jumping from a plane was dropping from a tower about 200 feet high. To do this we were placed in a parachute and attached to a wire which pulled us to the top of the tower. The tower had four arms sticking out from the top each having a number. one through four. After pulling four guys up there. some big shot standing safely on the ground would yell ... release number one. or number four or number something or other. If you were lucky. you might remember your number and be ready. Being ready was important because you had to guide the chute so that it moved away from the tower or else you could wind up in a broken mess by crashing into the tower. This was easy enough during the day. but they couldn't let it go at that so we had to drop from up there at night also. This became a lot more tricky because we were required to guide the chute away from the tower by looking at a light on the ground. When we reached the top this guy on the ground would yell ... number so-and-so do you see your light ... and if you saw it you said "yes" and the light holder would say ... release number whatever. This is where the problem started because you had to immediately guide the chute toward the light. When I got up on the number four arm I lost my cool just a little and when he yelled, "Number four do you see your light?" I screamed "yes" when in fact I didn't see anything. But, I knew that yes was supposed to be the right answer. The guy said to release number four and I pulled on those guide lines so hard that tower did not even come close. Despite the fact that I did not see the light I landed right on top of the fellow who thought he was so safe there on the ground.

As I stood there happy to be in one piece I heard the question ... number one do you see your light ... and the answer was yes. Release number one ... a moment of silence and then crash. screech. bam or something like that. Then a lot of people started screaming all over the place. Believe it or not their main concern was whether the chute was damaged. They seemed to care little for the poor dope who guided his chute into the tower. We quickly moved in to see who was dead or dying and found that it wasn't a dope and he wasn't dying. It was Private Peter Racich in fine shape and ready for anything except another trip up that tower.

By now we had been issued jump boots, and to say we were proud of those boots would be an understatement in a big way. A trooper is proud number one of his boots and then proud of being a trooper so that he can wear those boots. We were the only military types with authority to wear the jump boots though a few others tried and had them cut from their feet by enraged paratroopers. We tucked our pants into the tops of those boots and knew we could lick the world as soon as we got a chance ... the chance was coming all too soon.

Roger and I packed our chutes for the first time for real. The next day we would make our first jump. I rushed to finish the packing because I had permission to go into town to meet my aunt and uncle who had come to see me make my first jump. This was quite a thrill because they had brought my girl friend with them. I suppose they wanted to see me one more time just in case that chute didn't open. We spent a few hours together in Columbus, Georgia, just outside Fort Benning and then back to the base for me. I tried to sleep and probably did. The next day came quickly and turned out to be a windy day. We couldn't jump in this kind of weather, so we just sat around waiting. My aunt, uncle and Edie were there waiting too. Big deal. Finally, the weather got better, and we left for the planes and struggled to get the chutes on. We wore two chutes, the second was smaller but was designed to save your life just in case the big one didn't open.

We were soon airborne, 24 troopers to each plane, and headed for the jump field. On the first run across the jump field 12 of the guys were supposed to jump, and they did. I was in the second group, and I had a horrible feeling as I watched those boys leave the plane with nothing but a parachute and a lot of air between them and the ground. Those in the second group had little time to worry about the first group. Very soon the jumpmaster called for us to stand up and hook up. We lined up from the door of the plane in a line and hooked the static line to a cable in the top of the plane. We were not required to pull a rip cord because the static line hooked inside the plane pulled the back pack of the chute and pulled the chute from the pack, and with any luck at all the chute opened. As I stood up and hooked up, I felt as though I might faint. I wondered what I was doing there. Then I thought, "come on boy you can't give up now." That was the end of any doubt which might have been in my mind.

We jumped, and the most thrilling moment of my life came when I looked up and saw that beautiful white parachute billowing above my head. I took several pieces of paper from my pocket and dropped them hoping that the people on the ground would notice. But, evidently no one noticed. Floating down was a great thrill and the landing was smooth enough. The first one was over. My "family" went back to Ohio; and during the next four days, we made four more jumps and earned our paratrooper wings. When they gave us those wings we knew for the first time that we had really made it as one of the greatest, a real paratrooper.

Back to the land of sand and pine trees for more running and more jumping from airplanes while in flight. We ran and trained a lot and jumped six more times. Each jump became more difficult, and the feeling among the troops was that the more we knew about jumping the more frightening it became.

Jump number seven started out just like all the others, but about 50 feet from the ground my chute lost it's air or something. and I hit the ground so fast that those watching thought that I had had it. The ambulance came rushing over to pick up the pieces. The effort was wasted because I had made the best tumble and roll that my training had been able to instill in my mind. I felt no pain, and, in fact, I had not been hurt at all. If there had been any doubt about the need of all that training, I lost the doubt about half way through that long tumble.

The next big moment came as we prepared for our first night jump, We wondered how it would be since there would be no way to see the ground so that we could get ready for the landing. It was very important to have the knees slightly bent and the toes pointed slightly down just at the moment of landing. In the dark we would have to be ready for impact as soon as the chute opened. We had trouble finding the jump zone, and we became more concerned as we flew around trying to find the place to jump. We, troopers lost some faith in the Air Force as we sat there waiting for the pilot to find the spot to dump us. Finally, the red light came on which was the signal to stand up and hook up. In a matter of seconds the green light flashed and out we went. I found myself feeling for the ground with my toes and wondering what would happen when the ground and I did meet. Sooner than expected, I smashed into the ground in a pretty good position and was very happy to escape without a scratch.

Being a paratrooper was not all training and jumping. We did go into town occasionally, and some of the boys enjoyed themselves a little too much. No matter what we still had to be up and in formation around daybreak each day. On occasion. some of the boys were barely able to stand up. This plus the fact that we were a little late getting into formation would make the officers lose their cool. One morning the Captain really gave us a hard time and told us. "Tomorrow morning I want to see you here on time; when that whistle blows I want to see those doors fly off that barracks as you come out." We usually did what we were told. so the next morning the doors flew off as we smashed through them without bothering to open them. The Captain was surprised. I'm sure, but he didn't say a word ... just looked with wonder and a little pride.

Christmas 1943 was a few days off, and I was facing my first Christmas away from home. There was no chance of going home, so all that I and the many others who were a long way from home could do was look forward to a turkey dinner in the mess hall and a lonely time in the barracks. I sat there on my bunk looking kinda sad no doubt, nothing to do but get used to the fact Christmas away from home just had to be. It did have to be, but it didn't have to be all that bad because I had already received an early Christmas present. Well, maybe not a Christmas present really, but I had been promoted to Corporal. The Lieutenant who had bet me two dollars that I couldn't throw those hand grenades into all those targets had promoted me. I wondered if my baseball ability had made any difference.

Anyway, as I sat there in gloomsville, Ray Helms, whom I really didn't know very well, came up to me and asked if I would like to go home with him for Christmas. With some reluctance I accepted. This was the beginning of a lasting friendship. Only a few guys really become friends in the service, but Ray, along with Roger and to a lesser degree C. B. Jones, were to become closely related to my brief Army career.

Christmas 1943 was one of the most enjoyable ones I ever had. I went home with Ray, and his older brother, Troy, who was an invalid, and his parents who obviously were relatively "poor" people treated me as one of their own. I fell in "love" with the whole family. They gave me presents and lots of good North Carolina type food. I had also bought small presents for the family, and the Christmas cheer was all around the house. Christmas away from home was not bad at all.

Troy Helms, though paralyzed from his waist down, could move around the house with ease. His arms and shoulders were very strong and his mind was sharp and his attitude was the greatest. That boy, a little older that Ray and he was a joy to be with. He enjoyed life and seemed to be dedicated to helping others do the same. Mr. and Mrs. Helms were not far behind in this respect, and I was always welcome in their home after that beautiful Christmas and spent many nice weekends with Ray and his family.

February 1944

In the cold of winter we were again loaded into trains and transported to some God forsaken mud hole in Tennessee for a month or two of war games. This had to be the most horrible thing that could face a bunch of troops short of actual combat. The first night in Tennessee was spent in tents in pouring rain. We were wet, muddy and miserable. It gets cold in Tennessee in the winter and the rain made it almost unbearable, or so we thought at that time.

Prior to leaving Camp Mackall, I had been requested to volunteer for a special detail. To be forced to volunteer for anything is the worst thing that can normally happen to a G. I. However, I soon learned that this special detail for which I had been picked was the greatest break in my short career. I was pulled from that mud hole and sent to a big dry tent, temporarily promoted to Staff Sergeant, and given a job of helping to control and process so-called war prisoners back to their outfits after they had been "captured." I ate well and slept in comfort while my outfit was out in the mud, mess and snow. I felt guilty to some extent and wondered why I was picked for such great duty. I suppose I even feared that someone might have thought I was too soft to make it in the mud and cold, but that couldn't be the case because no one ever cared whether a G. I. could make it or not ... so just lucky was I.

After about six weeks of mud maneuvers, I learned that my Regiment, the 517th, was being returned to Camp Mackall. They didn't send for me, so I asked permission to be relieved from my temporary assignment so that I could rejoin my outfit. Rumors indicated that the 5l7th was to be sent to Europe; I didn't want to miss the trip. After two or three days of riding trucks and jeeps, I found the ole paratroop outfit camped somewhere in another Tennessee mud hole, though not nearly as bad as before. The guys thought I was crazy for coming back, and I soon learned how lucky I had been to miss the mess they had been through.

The food had been strictly field rations which was a bad way to go. Ray suggested that we go looking for a farm house in hopes of finding something to eat. We evidently thought someone would just take us in and feed us. Or, of course, we could get shot. Anyway, off we went in search of some form of civilization. We spotted a farm house and arrived just before dark. We knocked on the door, and a young wife came to the door and with relative calm asked what we wanted. We told her that we had been out in the field for a long time without good hot food and would like to buy something to eat.

She was alone with her two small children, but her husband would be home soon so she let us in and proceeded to cook eggs, potatoes and some other goodies for us. If she was afraid of US, it didn't really show. This made me feel great because I figured that Ray and I were two good guys. We really enjoyed talking with the little kids, and no doubt they were impressed by two rather dirty type paratroopers. Soon the husband came home and showed little emotion at finding two G: I.s there with his wife and children. I've often wondered how he and she really felt. The only thing that I will remember is their hospitality and kindness. Looking back to the days of World War Two, their actions were rather typical of the way people in many parts of the world treated the boys in the service. We ate and visited and gave them much more money than they wanted. They wanted none, but it was obvious that they had little enough for themselves. Thus ended the Tennessee maneuvers and back to Camp Mackall we went to go through our final phase of training prior to a trip to Europe.

We made a few more jumps, including one more at night, and we seemed to have a few more free weekends. I visited with Ray's family, and Ray and I met a few nice girls Who were remembered later only because they sent Cookies and letters while we were overseas. This, too, was a way of life in World War Two ... you could meet a girl one time, talk and visit briefly, say good-bye after knowing her only a few hours, and she would send cookies as though she were an old friend. Those Who missed those war days were lucky in a way, but they missed a nation-wide feeling of friendship that we may never see again.

May 1944

Back on the train again and this time leaving Camp Mackall for the last time. We arrived at Camp Patrick Henry knowing that our time had come to be shipped out. We were on our way to Europe.

While at Patrick Henry I observed my first real display of bad feelings between the blacks and whites. I knew there had always been a problem between the two races, but I had been spared any actual wild demonstrations of the hatred or whatever existed. I knew there were no blacks in the paratroopers, but I never really wondered why. Apparently, they weren't asked to join. Very likely, this had little or nothing to do with the fact that a small war started right there between the blacks and the whites. I was in the middle of it for a while with bottles, rocks, and a few other things flying through the air. I soon realized just how stupid this was and got the heck out of there fast. Some were not so lucky and landed in the hospital. I wonder if they took the blacks to the same hospital ... they bled the same color of blood, I noticed.

A few days later we were marched to the seashore where many of us saw our first ship. As we got nearer to the General Richardson, our ship, I smelled something very strange but nice. Perfume was all around us. What could this be ... maybe a good-bye party group or something like that. It was not really like that because that good smell was coming from about six hundred WACs (Women Army types) and their luggage which was soon hauled aboard by the boys in my company. For 14 days that boat never stopped rocking.

17 - 30 May 1944

With the WACs all settled aboard ship and the paratroopers all excited about the sweet company they made, we sailed from Newport News, Virginia, bound for Naples, Italy. Within 15 minutes there was only one WAC left free ... free that is from the clutches of a paratrooper. This extra one I kinda latched on to, or was it the other way around. Well, I needed a mother type, and she looked as though she might be looking for a son. She taught me a couple of card games; and after I recovered from the excitement of that, I started wondering what else could be done aboard ship. It was obvious that the WAC hunt was over because every one had one trooper hanging on and two more waiting on the side lines just in case.

Those of us with nothing better to do were required to go to the ship commissary for candy, gum, lifesavers, and other goodies for the troops in our compartment of the ship. We each gave our orders, and for two or three cents an item we could get most any type of sweets. Roger Bender and I noticed that many of the guys were so interested in chasing women that they never gave an order for the goodies. We decided to go into business for ourselves. We bought loads of stuff from the commissary each morning and strolled among the guys and gals selling it for two or three cents profit per item. In the two weeks on the ship we earned over one hundred dollars each ... and stayed out of trouble.

Our ship was one of about twenty in the convoy to Naples. Several of the ships were responsible for protecting the troop ships from submarines and German gun boats. The ships literally weaved their way across the ocean to avoid becoming a target for the German submarines. One morning we went on deck to find that we were all alone in the middle of the Atlantic. Our ship had engine trouble and had been left to shift for itself. After the engines were running again, we felt a little safer but still expected to be shot out of the water at any moment. What a waste of WAC that would have been. The ship's captain must have thought about that himself because he poured on the power and we sailed in a straight line and caught the other ships before dark.

On Memorial Day afternoon we landed in Naples Harbor and got off that boat as soon as we could. No self-respecting paratrooper could enjoy being on a ship except, of course, the six hundred or so who had a WAC for company. We marched through the streets of poverty stricken Naples and marveled at what we saw. It was terrible with beggars everywhere trying to get a few pieces of money to feed their families. Bomb destruction was evident on all sides. This city and her people had suffered long and hard under the German guns. So this was war ... war that the American people would not have to see nor endure. Large piles of brick and stone which was once beautiful buildings left no doubt in the minds of this bunch of G. I.s as to whether we were now in the war zone.

We were taken to our camp area which was down in a huge volcano crater. Ray and I bunked together and went into town together. The streets of the city were loaded with people selling anything they could get their hands on that someone else wanted. We had to fight them off. These peoples were slowly starving to death so any profession was considered honorable. The turning point in the war had to come for them with the coming of the American troops and the expulsion of the Germans. The people of Napoli would survive and partly so because we left several of our dollars there.

June - July 1944

Our stay in Naples was rather short since we were needed on the battle fields surrounding Rome. We were loaded aboard LSTs (Landing Ships Troops, I think) and spent one cool night lying on deck while we were being transported up the Tyrrhenian Sea. We landed at Civitavecchia, Italy, near Rome and. charged toward the front lines through dirt, rubble and. German prisoner s. Our first night near the front was very exciting. We could hear the guns firing in the distance and wanted very much to know what was going on, but could see nothing. The next morning we advanced toward the real war and soon found it. Bullets were flying all over the place, and I couldn't tell for sure just who my friends were. We managed to crawl under bullets to a barnyard and kept on crawling through the area where cows had spent long hours before. A lot of "dirt" won't hurt you I soon found out. I also discovered that hair started to grow on my chest (must have been the fertilizer ), and the hair on my head started to turn white. This I mean.

At this time I was the assistant squad leader which meant, among other things, that I had to bring up the rear of the column of troops. As we crawled through the cow playground, we found that we had to go down a hill to get to where we thought the Germans were. The guys up front started. down the hill through a fence. As I, along with the man in front of me, started over the fence, the Germans started shooting right into us. We crawled back into the cow piles. Oh! war is hell, we decided. The worst part of this particular battle was over the hill, so I decided that's where this other guy and I should be. I said, "Let's go." He said, "No." I asked why. He said, "I don't want to get shot." He had a point. I thought about that for a few seconds and decided that we would go anyway. He still wouldn't. So, I told him to crawl back into a cow pile and rot. I started down the hill and that boy changed his mind and followed. We were making very good time when a hail of bullets flew all around us. We fell like the best movie stunt man and rolled as far as we could. The Germans must have thought they had us because they stopped shooting. We got up and ran to where the other troops were, and I crawled behind a tree that immediately became the target of a machine gun. I crawfished out of there and hid the best I could as we fired our guns like a bunch of cowboys and Indians. Soon the Germans retreated and our first day of war was over except for an occasional shell burst nearby during the night.

The next day we were told to chase the Germans out of a small town. We had little success, so some tanks came to help us. My little group of about twelve troops were assigned to clear some buildings on a hill outside of town. We approached the buildings with more of the cowboy and Indian stuff and the Germans took off. It was here that I smelled human blood for the first time. Unfortunately, an Italian man who lived in one of the buildings had been badly shot. Other members of the family were praying and screaming and no doubt cussing us and the Germans at the same time. There's no way to describe the sorrow and futility that I felt at that time. We arranged to have our medics take care of the man and joined the tanks and other troops and stormed the town. Bullets were flying in all directions and what made it worse was the fact that the bullets could be seen going through the air. One of five could be anyway, because they were tracer bullets. Tracer bullets are on fire as they fly from gun to target. With guns firing so fast the air was full of tracer bullets, and we knew there were many times that many that made no light as they searched for something to hit. What a feeling not knowing for sure which way those bullets were going. Somehow, we made it, and the Germans left town in a rush. We were hungry and tired and expected to find a place to sleep in town. We were given some food and orders to move out. This was very disappointing, but we left the town and slowly moved into the hills. It was so dark that we had to hold to each other to keep from getting lost. This was frightening to say the least and the most eerie feeling I had ever experienced. Around midnight as we wormed our way through the brush on that hill, a most ghostly and ghastly light began to appear in the northern sky. Such a sight would have to be seen to believe, and coming under the conditions under which we were existing at that time, it was overwhelming. I have never seen such a sight and never expect to again. After what seemed like hours of fright and wonder, we decided this unbelievable, rolling light was the aurora borealis, or northern lights. We spent the night in the hills with Germans all around us, but we didn't bother each other and the next morning they were gone.

The battle of Rome was over, but we continued up the coast to Grosseto where we had our last big fight in Italy. This I remember because of C. B. Jones. We were in a tight spot for a while and had to do a lot of maneuvering to stay alive. I asked C. B. to go to a certain position and he screamed, "What are you trying to do, get me killed?" The strain of war was getting to the little guy. Most of us, including C. B., came through in good condition and were relieved and taken back to Rome for what we had hoped to be a long rest. General Mark Clark had a lot of good words to say for the parachute outfit that didn't jump into Italy, but earned our first battle star anyway for our part in liberating Rome and the surrounding country side. We ate our share of grapes during our tour through the area, and some of the troops raided a few too many wine cellars. That wine was terrible.

July - August 1944

My outfit, the 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment, was through with the Italian front in early July and was sent to the area of Frascati just a little southeast of Rome. Our mission now was to first of all get ready for the invasion of Southern France, but we had a few other missions also. These missions involved trips into the Eternal City ... Rome. We had made our mark at war, now we would make our mark at wine, or something like that. The Germans knew who we were. We even became the object of a discussion by Berlin Sal, the very famous German radio personality who tried to smash the morale of the American troops by playing sweet music for us over the radio, and telling us all the bad things she could dream up. To the men of the 517th she said, "You men of the Five-Seventeen are much better than we anticipate. But you are foolhardy ... you will lose men." Really, that wasn't a very brilliant statement, any nut would know that we would lose men, and the other stuff she said was true enough.

We pitched our tents in an olive grove and started working and playing. The playing was the most memorable, and the opportunity to see such historic places as the Vatican City, the Colosseum, the Victor Emmanuelle monument and drive a jeep along the Apian Way was almost worth the trip. I didn't seek an audience with Pope Pius XII, though some of the guys did. Rome was great, and C. B. Jones and I visited some of the more interesting spots. Also, Ray Helms and I went to a sweet shop occasionally. We liked ice cream, especially when it was served by two of the most beautiful dolls in Rome. Unfortunately, those dolls had a very protective dad who watched us like a hawk. Oh well, we enjoyed looking anyway.

Some of the most interesting things happened around the olive grove. We had a lot of visitors, mostly mothers looking for a handout to help feed their families. These women would come at each mealtime and literally compete for scraps of food leftover from our meals. They would tell stories about each other in hopes that we would chase the "bad" one away, thus making more scraps available for the "good" ones. The favorite "bad woman" story was to say that the other gal liked Germans. We ignored the tales and made them line up and share the wealth. We sometimes looked for a little extra food ourselves. We would take gallon cans of fruit salad or other fruit from the mess hall and eat it in our tents. One night we stole, I mean took, a few cans and later discovered it was apple butter. What a waste ... we gave it to the good gals ... and the bad gals too.

We were also known to "borrow" jeeps and trucks from the regular Army, because paratroopers just don't have such things. We ride planes, so who needs a jeep? We did. After all, how were we expected to get around Rome. We even borrowed a few and rode them into combat during our battles. I lost a beautiful fountain pen and a lot of other stuff when we drove one into a German battlefield position. We got away, the Germans got the jeep and all of its contents. Such a war.

All was not fun and frolic in and around Rome since we were there to get ready for a jump. We studied maps of our jump zone which we hoped to hit in France. We sprayed our jump suits with camouflage paint until we must have looked like the leftovers of Satan's Society, straight from the hallowed halls of Hades.

On the l5th of August we were told that the time had come ... we would jump in France that night. We sat around in small groups, ate all our candy (just in case we didn't make it, we would leave none of those goodies) and talked about the coming jump. In a group of four, Private Lemen said, "The odds are at least one of four of us will die in this jump." No use to argue with the odds, so we tried to think of more pleasant things.

About midnight we dressed for the trip across the Tyrrhenian Sea and our jump in France. I had over 60 pounds of explosives tied to my legs because blowing-up bridges and things was to be one of my jobs. I also had all my food and water, which was to last for a couple of days, plus hand grenades, tommy gun, bullets and actually everything that I owned. I was so heavily loaded that walking was almost impossible. It was unbelievable the amount of stuff I had to jump with. Most of the troopers were about the same, but the explosives made my load the hardest to carry. I nearly fell on the way to the plane, but somehow I managed to climb aboard with a lot of help. Rome had come and now it would go. Perhaps it would be best to say that we had had the good fortune to survive and come to Rome and now we were faced with the sadness of departure. Our planes, the C-47's, took off in total darkness, and the lights of Rome soon faded away.

CEAugust - November 1944

The planes, dark and packed with paratroopers, nosed into darkness and out over the Tyrrhenian Sea carrying us to an unforgettable adventure along the Riviera to the foothills of the Alps. Not much was said as we roared toward France and a night jump that would make those practice jumps look like a moonlight outing. I laid my head down on my reserve chute which was fastened across my belly but pushed nearly up to my chin by all the stuff in my pack which hung below the chute. I thought of many things; the rugged training, the practice jumps and tried to remember all the things necessary for a successful jump.

Never had I been required to jump with so much weight, and I knew that I would need a lot of luck to make it. We had a long way to fly, and the danger from German fighter planes added to the discomfort of the flight. To this point I had never landed in a plane and was eager to get to the jump zone and make jump number twelve.

About three hours after takeoff, we were jolted from our individual thoughts by the signal to get ready to jump. The darkness was overpowering, but we were ready. The red light flashed; we struggled to our feet and hooked our static lines to the cable running down the middle of the plane. We checked the equipment of the man in front of us to assure that everything was secure. I was well back in the line which meant that I would leave the plane nearly last. This is no big thing except trying to carryall that weight down the isle of a bouncing plane was a little tricky. The green light flashed on, and the line of troopers pushed toward the door. Whether by accident or intentionally, the man in front of me went past the door rather than turn right and jump. I grabbed this man with my left arm, pulled him to the door and threw him out. In doing so, my arm became tangled in one of our static lines as I went out right on top of him. I raised my arm above my head and felt the line move up my arm which probably saved serious injury or loss of an arm. The chute opened with a tremendous jolt. The sensation of floating was comforting, but the total darkness made this a very lonely journey down into I knew not what. The only sound was the departing planes on their way back to Rome and maybe to the sweet shop where the dark-eyed sisters served cookies and ice cream. As we came closer to the ground, the sound of gun fire added to the excitement of the night. As the guns were fired, the flash of light from the gun barrels let us know that the enemy was near. It also told me that the ground was near. The darkness was still total, so I pointed my toes slightly downward and flexed my knees. Suddenly, without warning, I hit the ground extremely hard. Both legs felt as though they were on fire. I moved them and was satisfied that no bones were broken. I ripped the parachute harness off, took out my compass and lined myself up toward the Northeast and started walking.

At this point I saw nothing but a few trees. I was glad to have lucked into an open spot for my landing but felt so alone because none of my buddies were to be found at that moment. Shortly, three or four of us ran into each other and headed for the assembly point. Nothing seemed the same as the maps we had studied back in the olive groves. We could not find the designated assembly point. We later learned that the plans were changed while we were in flight, so we were dropped several miles from the original drop zone. They didn't bother to, or could not, tell us. We later learned that our planned landing zone had become known to the Germans, and they were waiting for us. We were lost but lucky not to have been dropped into the waiting enemy. After the smoke of battle cleared, we were shown our original jump zone which contained sharp sticks pointing into the air along with barbed wire and other things meant to welcome us. Also in abundance were the bloated bodies of dozens of dead Germans. What a sight.

But that's ahead of the story. We are still lost back in the new jump zone and very disorganized. Still unaware of where we were. those of us who had managed to find each other were following the compass. In total darkness we ran head on into an area filled with foreign voices. we backed off not knowing at the time whether they were French or German. We staggered around under the weight of our over-loads until daybreak and then threaded our way through Germans. French and farm animals. We could not find an officer or sergeant of any kind. As a corporal, I was the senior to the others, so I took over and started searching for familiar faces. Shortly after daylight we found a captain and a group of men. We thought we had found a leader. but soon found that he was a mess officer and didn't know beans about leading troops in combat. After being under enemy fire for a few minutes and seeing this captain in panic. my little group decided to get the heck out of there. We finally discovered a large group of men in a wooded area. These were our outfit and soon most of us were together. I learned that Ray Helms had landed on top of a French farm house and went through the roof. He was knocked out and came to in the company of a startled family of Frenchies. Roger Bender and his squad, who were in charge of our mortars (mortars are rather large guns that shoot bomb-like shells), were unable to find the darn things after they landed. The mortar packages had lights on them but somehow could not be seen. Roger and his boys went back to look for them and managed to locate them an hour or so later. By this time we were knocking off a few "krauts" and taking over large areas of farm land near the jump area. I used some of my explosives to blow a bunch of trees off the road. I was glad to get rid of some of the weight, because my legs still hurt from the impact with the ground.

In the early afternoon we stopped on a hill and set up a defensive line to hold back the Germans. Roger placed his mortar nearby and blasted away at the enemy in the valley below. They fired back with tank guns and artillery. The Germans were coming into the valley by the hundreds, and we could do nothing but watch. They moved a tank up close enough to really blast us. Private Lemen was killed by a direct hit from a tank gun. He had in a way predicted his own death before we loaded into the planes the night before. Others were being wounded, and every minute you thought that you might be next. We dug holes into the ground and stayed in them for protection. The so-called fox hole or slit trench saved thousands of lives during the war, and I as well as all others were to spend many hours in holes in the ground. Humans or animals of the forest, I hoped that God could tell the difference. In the hole next to me was the guy whom I had thrown from the plane a few hours earlier. I wished several times that I had left him in the plane. He whined and moaned constantly with fear. He asked me over and over if we were going to make it out alive. I now thought he went past the door on purpose, and tried to understand his fear which really was not so difficult to do. I had seen men who could not even jump from a tower at Fort Benning though they really tried hard to do so. They knew that they would not die, but some fear from within would not let them jump. So, what is there to be ashamed of when you experience fear when you know death, or the means of death, is all around you.

We were really in trouble and we knew it. We fired at the Germans, and they fired back. We could see them coming and massing their troops in the valley just a few hundred yards from us. We had nothing big to hit them with. Roger, with his little mortar tried, but I think that thing just made them mad. Darkness was coming and we knew the end was near, they would attack just before dark and tear us to pieces. We waited and wondered why they did. It was 6:00 P.M. when suddenly from our left came the roar of guns, hundreds of guns, big guns. The valley below us was literally covered with a barrage of artillery fire from guns of an American Artillery Company which had moved in to help us. The earth shook, the noise could not be equaled by any concentration of thunder. The enemy was dead or so stunned that they no longer wanted to fight. As we captured those still alive, they told us that they were ready to attack us when the artillery barrage from our guns came rolling through the valley. This battle was over. Tomorrow there would be another, but that night we slept well. As usual, the earth was our bed.

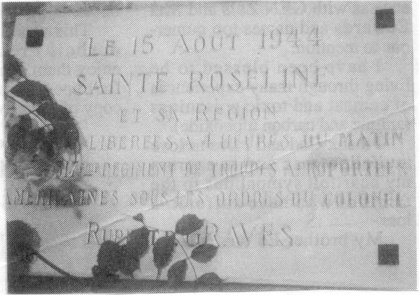

The next three weeks were busy ones for the men of the Five Seventeenth as we pushed our way up the coast of Southern France. We had the Germans on the move as we liberated city after city which had been held by the Germans for many months. The fondest memory of this march to the Maritime Alps was the sweet aroma of perfume as we charged through the cities where it was made and stored* No doubt we shot a few holes in storage tanks, but not all of that sweet "smell of victory" came from storage tanks. We were greeted in every city by those lovely French girls and some of the old gals also. They loved us, but we didn't have time to love them. We just kept on moving. Sure, war was hell.

| * Grasse was the sweetest. |

We moved fast, often hungry, thirsty and sleepy. On one occasion we had to restrain some troops from eating sugar beets. These are not good to eat, but I never found out whether they would kill a human or even make him sick for that matter. Our only concern was for the paratroopers who aren't really human ... sugar beets would probably make them at least a little ill. On one particular rush through the farm lands of France we came to a river. We were on one side, the Germans on the other. We had no way to cross so we stopped and waited for the food trucks to catch up. When they did, they brought only field rations. This cold stuff kept us going and was appreciated.

On this occasion the trucks brought candy, gum, and extra smokes for those who wanted them. This time, as usual, the goodies were few, so we carefully split them among the men. Several times while in the field I split candy bars and broke sticks of gum into two pieces to assure that each man in my squad had at least a small share. The guys would sit there like little children and watch with anticipation. A person's feelings at a time like that cannot be described in words, so I'll just drop the subject.

As we sat there on our side of the river, we welcomed the rest and looked forward to a good sleep. This was not to be. Our company was selected to cross the river under cover of darkness. We were to find out what the Germans. had on the other side. This was the most dangerous mission assigned to any of the 517th up to that time. We were expected to get clobbered. Naturally, we ate all our candy ... just in case we didn't make it. Didn't want to leave any of that good stuff for anyone who might find our bodies later. We said a sad good-bye to those who were to stay behind. They gave us their best wishes and left us to prepare for the crossing.

A Frenchman had been found who would lead us down the steep and dangerous cliff and across the river. We were told that the water would be about up to our armpits in spots. This wasn't so bad At about 2:00 A M, we started down the cliff toward the river The trail was suitable for mountain goat,. but somehow that Frenchman led u, to the water during total darkness. The guy. whoever he was, who said the water was only up to the armpit evidently didn't check where we crossed or else he was at least seven feet tall. We hadn't gone far when we were in over our head,. We lost a gun or two but made it to more shallow water. Every moment we expected to receive a welcome from the German gun,. We were ignored because the Kraut, knew anyone with any brain, at all would never try to cross that river at night They were not aware of the fact that we were paratrooper,. thus not very bright. We sneaked in behind the German lines and hid for a while to get organized. A French family brought us a big pot of stew which was just about the best stuff we had in France.

We made our way nearer the town, La Rocquette I think, and dug in on a hill still not knowing where the Germans were nor how many there were of them. In mid afternoon I had to go to the bathroom ... of course, there was no bathroom on the battlefields of France, but that was a way of life in combat. At any rate, I had to go and as I went or was going or whatever ... I heard some more familiar thuds. The next thing I knew bullets were flying under my feet. The expression "caught with my pants down" is the best way I know to express my plight. This didn't slow me down much. In a couple of seconds I was back in the slit trench with my bare knees sticking up and bullets bouncing allover the place. I wiggled back into my pants and yelled, "Let's get out of here." We started running up the hill, and I dropped my tommy gun. I scrambled back for it and finally made it over the hill in a hail of bullets. Obviously:, the Germans were a long way off because they missed us and we could not hear their guns fire.

Though we could not hear their guns we knew where they were. They were in this small town which was situated on a cliff overlooking the river. A beautiful place to be. Unfortunately for the Germans, we were behind them and even though they had fired at us they didn't seem to realize the fact that we were there. They might have thought we were French. Whatever their problem, we sneaked in behind them and from cover of trees and grapevines we watched them milling around the town. As we watched, more of their troops marched into town.

They assembled in the court yard and some were lying around on the grass when we opened fire with all the guns we had. Those Germans were in panic. Some fought, some ran inside buildings, and some jumped over the cliff. One of their mortar shells landed in our squad.

The shell fragments flew in all directions hitting Ray Helms and one other man. Ray was the squad leader, and I was the assistant. We did what we could for Ray and Private Duncan and continued toward the city.

The fighting was wild, but we seemed to have profited by the element of surprise. Within an hour we had cleaned out the town. Several enemy were dead and about one hundred were captured. The prisoners thought we were going to kill them, I suppose, because some of them begged us not to shoot them. Others offered us money. We assured them that they would be treated properly. They were lucky and apparently happy at this point, but I think we were the lucky ones because we had only the two wounded and no deaths.

Sergeant Craig, who had bet me two dollars in the hand grenades throwing incident and lost a little blood in our wrestling match back at Camp Mackall, lead us in this battle. For his outstanding leadership he was given a battlefield commission. We had lost a good Sergeant, but gained a good Second Lieutenant. Of much less significance, I replaced Ray as squad leader. There was no thrill in this for me, because Ray was my best friend and his injury was rather serious.

To make things worse we could not get him out to a doctor. We were still behind enemy lines. Help did not come until the next day when our troops on the other side of the river were able to cross and find us.

After the battle we were hungry, but had no food. There was no way of getting any either until the other troops got through to us. Should have saved some of that candy we had eaten the night before. I'll never forget that night. I was so hungry. The only thing I had which was even remotely associated with food was a package of lemonade powder. A German prisoner gave me some "hard tack" type stuff. This was somewhat like little rocks, but might have been some sort of bread. I mixed the lemonade powder with some stale water and drank it to help melt the German hard tack. Under the circumstances, I believe this tasted better than the stew the French family had given us in the morning. We remained near the town that night, keeping a sharp look-out for more Germans. As luck would have it, none came.

During the night, as usual on guard duty, one or two men would watch a small area for an hour then wake someone else who watched for an hour, and on and on through the night. One of our troops had finished his hour of guard duty and tried to wake a guy to take his turn. The guy would not respond. After a slight hassle, our troop discovered with some surprise that he had been trying to wake a dead German.

It was a welcome sight the next day when our troops arrived from across the river with food and a jeep to carry Ray and the other wounded man back to safety and medical attention. I know we all wondered who really were the lucky ones. I think most of us would have traded places with Ray. It was often said that the real lucky ones got shot early ... of course, a nice clean wound had to be part of the deal. So, there we were the "unlucky ones" on the march again. Charge! That's what we did day after day, chasing Germans allover Southern France ... at least it seemed that way.

In early September our charge came to a halt overlooking the Sospel valley. In this valley lay the lovely. but seemingly forbidden City of Sospel. The city was forbidden in that we could not get into the place. German forts. or more correctly stated. French forts manned by Germans kept us out of town. We first saw the city late one afternoon from a small mountain which jutted out toward the valley. I was one of the few who went to the vantage point to view the sights out that way. We immediately drew gun fire from the Germans and quickly got out of there. We dug our holes and set up a defensive line to our front. No enemy showed up. but their big artillery shells dropped in all through our positions. We had even strung cans on wires to make noise if the Germans had come sneaking in. I was nearly lifted from my shallow hole on several occasions during the night. I had never experienced such concussion from shell blasts. The next morning I crawled from my hole and rolled up in my rain coat and shelter half to rest on the ground. The German shells had stopped at daybreak, and we felt safe. A short time later we heard something in the outlying area. so went back underground. A few bullets flew around us and I heard a thud nearby. Later. I found that the thud was caused by a bullet as it tore through my "bed roll" which I had left when I jumped back in the hole. Lucky for me I had vacated that spot. It was obvious that this place was not the most desirable place to live. That morning we found several dead or wounded among our troops. The company commander decided to move back behind the mountain. This was a great idea as far as I was concerned. but my feeling of relief was short lived. The commander assigned me and my squad the responsibility of staying right there as an outpost to watch for the enemy and guard the area. A group of boys from Hawaii were left there with us. These guys had an anti-tank gun with a truckload of shells just in case the Germans decided to come in with a tank. The Hawaiian boys numbered four or five and my squad was made up of eleven pretty tough characters ... tough anyway.

We felt rather lonesome as the company pulled out and left us. Me, a 19 year old kid with some others about the same age, along with some who were in their twenties. We also had one convenience of home, a telephone. This phone was in a shallow slit trench which became my home for the night. Shortly after dark, the phone rang. The Company Commander was on the phone with some exciting news. Germans had been spotted coming up both sides of our not-so-sacred mountain. We were to stand our ground and keep the guys behind the mountain informed. He reminded me that if we lived through the night we could come back behind the mountain the next morning. He may not have put it just like that, but we could be assured of relief the next day. He also told me that our own artillery was going to start blasting the Germans who were approaching us. This sounded better. As he hung up, the shells from our guns from behind the hill began to whiz over our heads into enemy territory. We felt safe because this would very likely drive the Germans back. However, in a matter of seconds these shells started dropping right into our position. The truck loaded with anti-tank ammunition was blasted by one of the shells. All hell had broken loose. I called the company as the shells kept coming in. I told them that we were being torn up by our own guns. While I pleaded with them to stop those guns, the boys from Hawaii and the guys in my squad were trying to find a deeper hole to crawl into. My hole was shallow and gave little protection. I was hit in the chest by something blasted my way by a shell burst, but it only hurt a little. Three men from my squad were lying there in the road in front of me begging, "Gene, make them stop." I wondered if they thought I was talking to the girl next door. I told them to get the hell in a hole, I was doing all I could.

Several minutes later the blasting stopped. We checked the troops and equipment and found that the only victim was the truck. Someone swore that the Hawaiian boys had turned white during the early stages of that mess. At any rate all was quiet for the moment. Our only problem was the fact that the Germans were still coming.

As we were getting regrouped, the phone rang again. This time it was the captain who directed the artillery company. He and my commander wanted me to direct the artillery fire on the Germans. I told them I didn't know anything about directing artillery fire, but they insisted because their directors, or whatever they caned them, had all been knocked out of action up our way the day before. The artillery captain gave me some instructions, and I gave him my first "order." I told him to raise those gun sights a few points and start firing. If they cleared us, we could take it from there. They did so and the shells missed us with no problems. This captain told me to go out in front of our positions and observe where the shells were falling. This didn't appeal to me one bit, but I took my rifle and walked into the darkness, expecting every moment to be shot. The artillery blasted away, but I couldn't see where they were landing those shells. I got back to the phone and told the captain. He said that he would have the gunners fire some smoke shells. I asked him how he expected me to see smoke when it was as dark as the inside of a cow. He informed me that smoke shells make a much bigger blast of flame when they exploded, so I might be able to see the flash. Back into the darkness time after time as I tried to direct the fire. Then one of our officers from another company got on the phone and said I was directing fire into his troops. We discussed this for a while and decided this was not the case. So, back out into the darkness some more, and I still didn't know where the Germans were, but expected one to get me any moment. Soon we had the fire going the way we hoped was right, so I settled down in my hole and prayed that the Germans would not get to us. They didn't.

The next morning an officer and a group of others came to our position. They wanted to see the guy who directed fire last night. I knew then that I had killed some of our own troops. I thought I knew that is. That was not the case. They told me that we had done a good job and blasted the hell out of the Germans. Later, I was awarded the Bronze Star Medal along with the following citation:

"Under the provisions of AR 600-45, EUGENE L. BRISSEY, 35803600, Corporal, Company "E", 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment, is awarded the Bronze Star Medal for heroic achievement in action against the enemy near Col de Orme, France, on 11 September 1944."