A History of the 517th Parachute Combat Team

Copyright © by the 517th Parachute Regimental Combat Team Association.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Published November 1985.

First Edition.

Senior Editor, Clark Archer

Illustrations, Chris Graves

Published by the 517th Parachute Regimental Combat Team Association.

6600 Josie Lane

Hudson, FL 33567

Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number 85-82102.

International Standard Book Number 0-9616015-0-7.

Printed in the United States of America

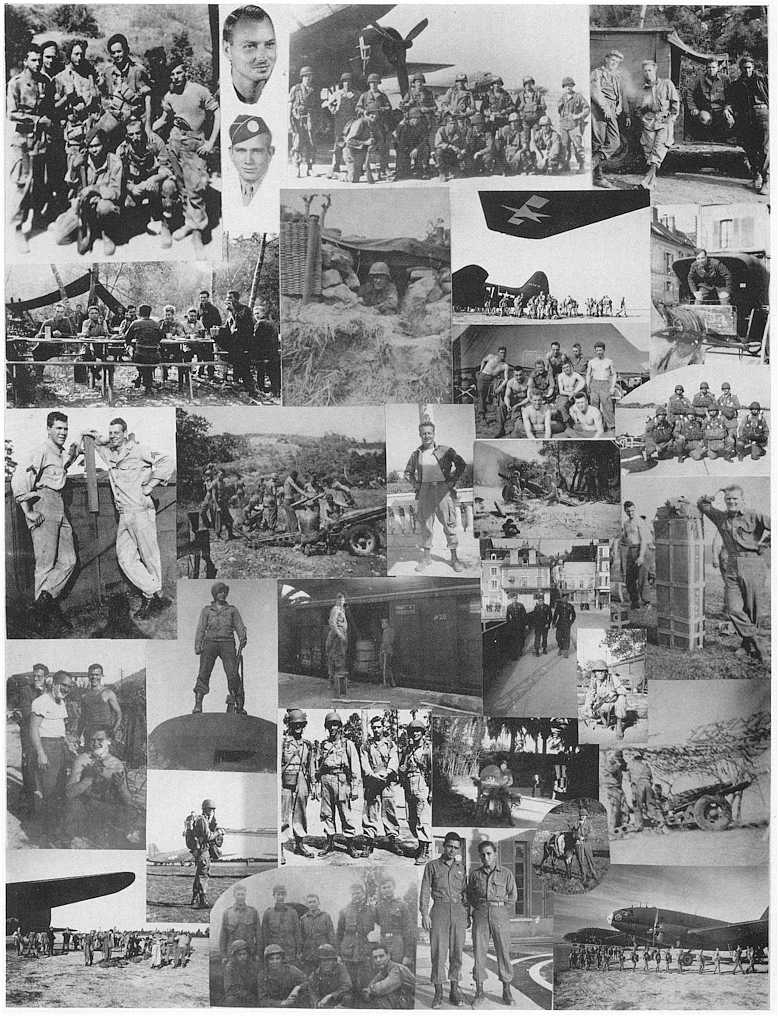

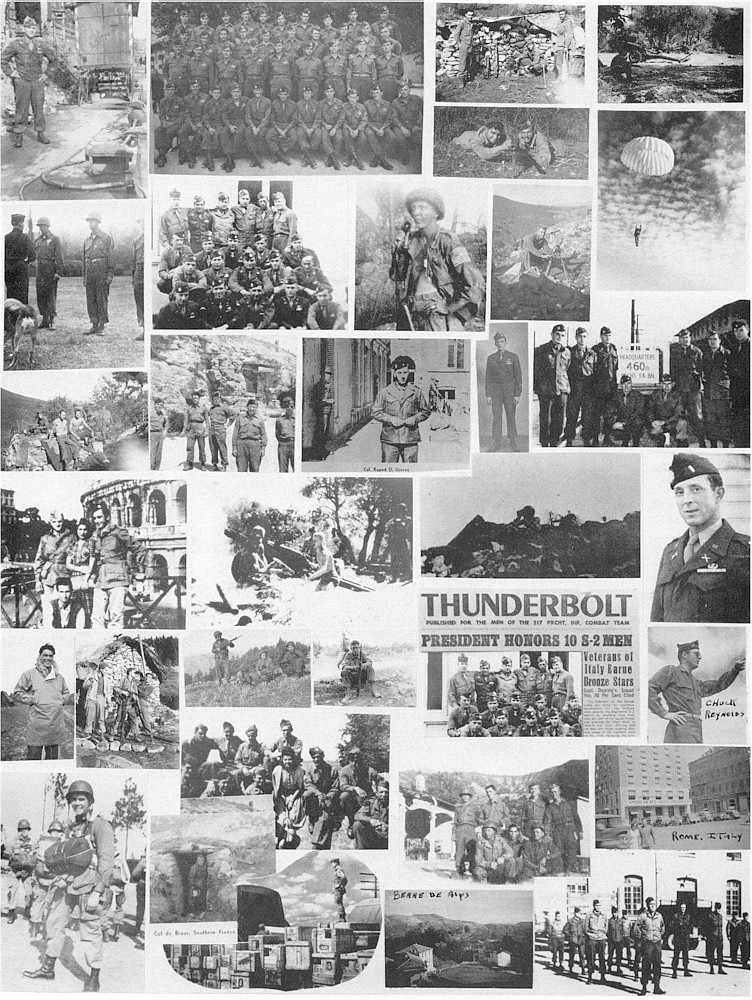

The 517th Parachute RCT Association, under President Charles E. Pugh, is proud to publish this history.

The Association was founded shortly after World War II to preserve the bonds of comradeship that were forged on the battlefields of Europe, Veterans of this Association served in the Rome-Arno, Southern France, Rhineland, Ardennes-Alsace and Central Europe campaigns.

517th Parachute RCT Association

William J. Lewis

Secretary/Treasurer

The Association's mandate to develop a unit history contained several key requirements. First, the history be complete, accurate and unglorified. Second, there be a reasonable balance between items of military and human interest. Finally, all material selected for publication be based on credible documentation.

These criteria have been met.

Clark L. Archer

Editor

This history is dedicated to all who served in the

517th Parachute Regimental Combat Team

517th Parachute Infantry Regiment

460th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion

596th Parachute Engineer Company

This

is the story of the experiences of a separate parachute regimental combat team.

It is written, not only for the surviving members of the combat team, but for

their children and descendants. For those who gave their lives in these

campaigns, it may serve to let their families and relatives know of their

contribution. As many readers of this account may have been very young or not

even present when Hitler's Nazi armies overran much of Europe and parts of

Africa, it may also serve to let them know of the sacrifices that were made at

this time to overcome a determined enemy and to show the necessity of being

prepared against future aggression.

This

is the story of the experiences of a separate parachute regimental combat team.

It is written, not only for the surviving members of the combat team, but for

their children and descendants. For those who gave their lives in these

campaigns, it may serve to let their families and relatives know of their

contribution. As many readers of this account may have been very young or not

even present when Hitler's Nazi armies overran much of Europe and parts of

Africa, it may also serve to let them know of the sacrifices that were made at

this time to overcome a determined enemy and to show the necessity of being

prepared against future aggression.

The members of this combat team were young Americans of that period where even the most senior battalion commanders and regimental staff officers were young graduates of ROTC with a year or two of service.

What motivated these people to close in against well defended enemy machine gun positions, often manned by elite Nazi SS troops, may be open to question. Perhaps initially it might have been patriotism, but later this was replaced by comradeship acting as a sort of life force inducing a loyalty that transcends friendship. They simply did not want to let their pals down. Good physical conditioning from long, hard training, and the spirit of optimistic youth willing to take a chance was also another probable ingredient.

It should be noted that although parachute units were only organized and equipped for short airborne operations and withdrawal, that they were usually kept in combat over long periods of time without proper transportation or supporting artillery. This was probably due to necessity as well as the ability of the parachute units to operate successfully with the light equipment issued to them.

Although I have served with many different military organizations during my years of service, I have never served with any group that, compares with the spirit, the initiative, the physical qualifications and comradeship of the 517th RCT. I feel grateful for the opportunity given to me to take this unit overseas and bring it home.

We are indebted to those individuals who spent the long and painstaking hours devoted to compiling this story.

Rupert D. Graves

Colonel, U.S.A. (Ret.)

A History of the 517th Parachute Combat Team

Part One

Trial By Fire

This has been a labor of love but it has not been done alone. I want to express special thanks to Clark Archer, Charles Pugh, and Bill Lewis, whose encouragement and support made this history possible; also to Joe Miller and Nolan Powell, who spent days and weeks at their own expense tracking down records at the National Archives and elsewhere. Grateful thanks and appreciation are also extended to the following, who contributed material and provided helpful comments:

|

John A. Alicki |

Leroy Johnson |

This history is intended to be a memorial to all who served in the 517th Parachute Regimental Combat Team. It has been possible to mention only a few men by name. To all the others ... the vast majority of the Combat Team, who did their duty bravely and well ... my sincere apologies.

Charles E. La Chaussee

In early 1943 the United States had been at war for a little over a year. The future was cloudy. How long the war would last and its final outcome were uncertain. Although Japanese expansion had been halted in the Pacific, it was still a long way to Tokyo. The Germans held all of Europe and were deep within Soviet Russia.

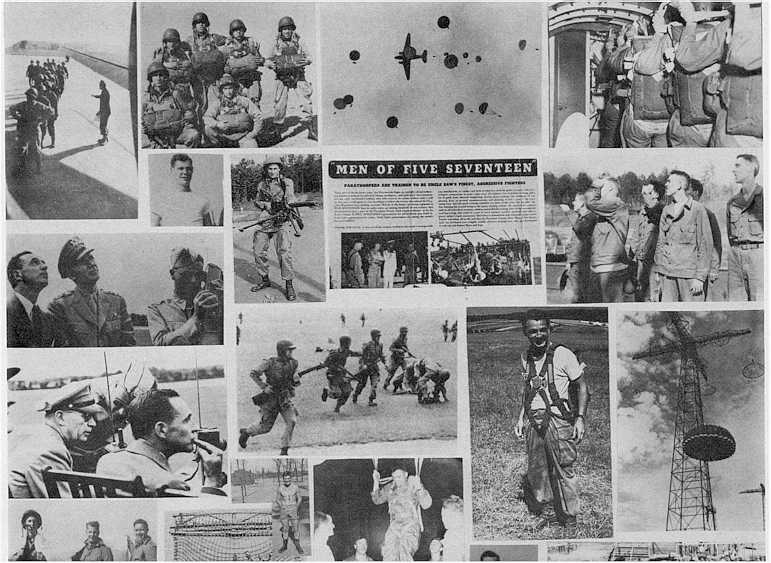

This war was far different from its predecessor of 1914-18. The tank and the airplane had restored mobility to the battlefield. American airborne forces underwent a vast expansion, growing from a parachute test platoon to five airborne Divisions and several smaller units.

The paratroopers were a new kind of soldier, trained to jump behind enemy lines and fight without outside help until relieved. They were brash, cocky, self-reliant, aggressive individualists, and a great deal was expected of them. How well some of them met those expectations is the subject of this book.

The 517th Parachute Regimental Combat Team, organized relatively late in the war, was destined to play a major role in the campaigns that led to the total defeat of the German Army and the liberation of Western Europe.

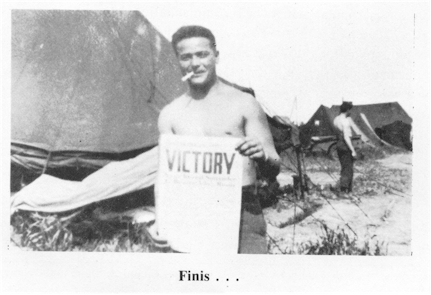

Standing Alone*

|

* "Standing Alone" is the meaning of the Cherokee Indian word "Currahee." |

The story of the 517th Parachute Regimental Combat Team begins with the activation of the 17th Airborne Division on March 15, 1943. The Division's parachute units were the 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment, the 460th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion, and Company C, 139th Airborne Engineer Battalion. The 517th was at Camp Toccoa, Georgia; the 460th and C/139 were at Camp Mackall, North Carolina.

For the next several months

all men volunteering for parachute duty at induction stations throughout the

United States were sent to Camp Toccoa. The 517th was charged with screening the

volunteers and assigning those qualified to either the infantry, artillery, 517

PIR Commander 1943 or engineers. Officers of the 460th and C/139 were placed on

temporary duty at Toccoa to help with the screening, and men assigned to those

units were sent to Camp MackaIl.

For the next several months

all men volunteering for parachute duty at induction stations throughout the

United States were sent to Camp Toccoa. The 517th was charged with screening the

volunteers and assigning those qualified to either the infantry, artillery, 517

PIR Commander 1943 or engineers. Officers of the 460th and C/139 were placed on

temporary duty at Toccoa to help with the screening, and men assigned to those

units were sent to Camp MackaIl.

As units filled up they were to be given basic training at their home stations and then sent for parachute qualification to Fort Benning, Georgia. After jump training all units, including the 517th, would join the 17th Airborne at Camp Mackall.

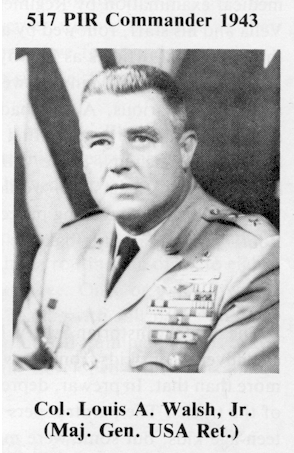

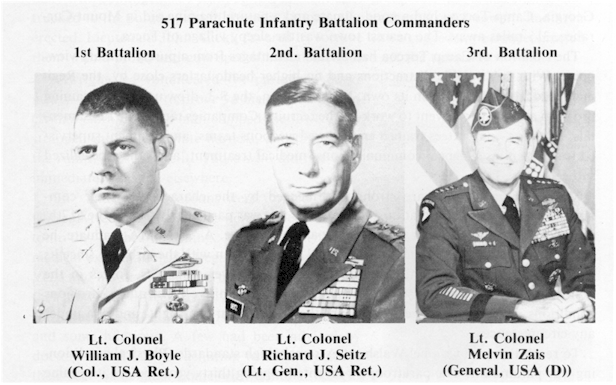

Receiving and screening one to two hundred men a day was a pretty big order for the 517th. On activation the Regiment had a total strength of nine officers, headed by newly-appointed commanding officer Lt Col Louis A. Walsh, Jr. They were joined three days later by the "cadre" under command of Major William J. Boyle, bringing the Regiment's strength to about 250.

Two days before the cadre's arrival the first trainload of parachute volunteers had pulled into the railroad station at Toccoa, early and unexpected. The nine officers met the train, drove the recruits to camp in borrowed trucks, issued some clothing and bedding and--with some help from the Post garrison--cooked and served them their first meal.

They were the first of many. Through the Spring of 1943 trains arrived at Toccoa daily with contingents of from 50 to 150 men. Each group was met at the station and trucked to the parade ground where a 34 foot tall parachute "mock tower" had been erected. Lieutenant John Alicki, favored by fortune with a rugged appearance, greeted them with a blood-and-guts speech intended to scare off the timorous.

"Awright, ya volunteered for

parachute duty, now's your chance to prove ya meant it!" Still in civilian

clothing, each man climbed the tower, was strapped into a parachute harness, and

tapped on the rump. Most made it. Those who did not were immediately headed

elsewhere.

"Awright, ya volunteered for

parachute duty, now's your chance to prove ya meant it!" Still in civilian

clothing, each man climbed the tower, was strapped into a parachute harness, and

tapped on the rump. Most made it. Those who did not were immediately headed

elsewhere.

"In" and "out" platoons were formed. Those who survived the mock tower went to the "In" platoon for further screening, This consisted of a medical examination by Regimental Surgeon Paul Vella and his staff, followed by an interrogation by their potential officers as to why they had applied for parachute duty. Many answers were interesting and some hilarious. A few had been advised by doctors to take up parachuting to help overcome their fear of heights, Some with criminal records had been told their slates would be wiped clean. Those failing the screening process were sent to the "out" platoon and the balance assigned to units.

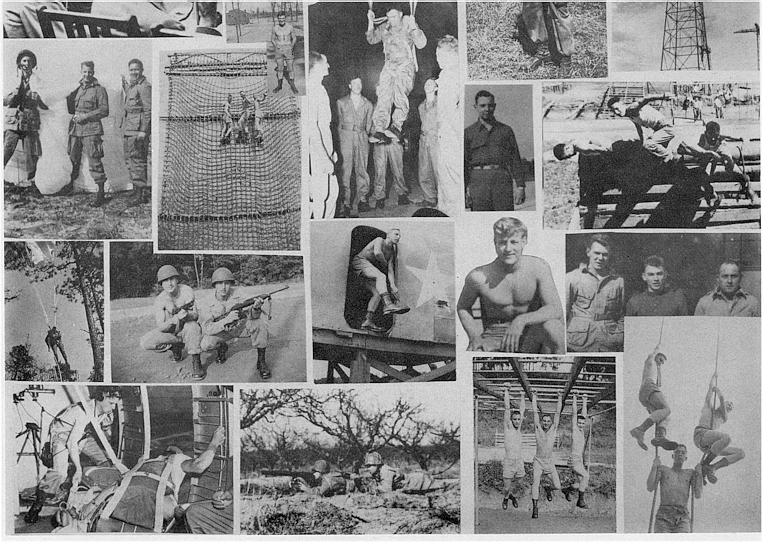

The military historian S.L.A. Marshall described the American WW II paratroopers as "adventurous kids from the wrong side of the tracks." This was close, but they were more than that. In prewar, depression America there had hardly been any "right" side of the tracks. The paratroopers came from all social and economic levels. Most were teen-age kids, but some were married men in their twenties. There were roughnecks and brawlers, but also some saints and scholars. The common denominators uniting them were willingness to take a chance and refusal to admit there was anything in the world they couldn't handle.

As men assigned to the artillery and engineers moved to Camp Mackall the infantry began basic training. Camp Toccoa had been a National Guard summer training post called Camp Toombs. With the coming of World War II it had been taken over by the Federal Government and retitled.* High in the mountains of northeastern Georgia, Camp Toccoa had a good climate and a natural training aid in Mount Currahee, 3 ½ miles away, The nearest town was the sleepy village of Toccoa.

| *"Toombs", although the name of a distinguished Southern soldier, is a little on the gloomy side. |

The isolation of Camp Toccoa had certain advantages from a purely military view-point. With few outside distractions and no higher headquarters close by, the Regiment was free to develop on its own. Major Paxton, the S-3, drew up a basic training program and the cadre went to work on the recruits, Companies taught the fundamentals, battalion committees trained crew-served weapons teams, and regiment supervised training in intelligence, communications, medical treatment, and other specialized subjects.

Military organizations are strongly influenced by the character of their commanders. Because of its isolation and greenness this was particularly true of the 517th. At age 32, Louis Walsh was young, cocky and aggressive. A '34 USMA graduate, he was the first in his class to make full colonel. He had been with the airborne since its earliest days and had spent three months as an observer with U.S. forces in the Southwest Pacific, Having seen combat in its most primitive form under atrocious conditions, he was determined to prepare the 517th to survive, fight, and win under any circumstances.

To reach this goal Colonel Walsh set extremely high standards. Physical conditioning was paramount. The paratroopers invented jogging thirty years before it became popular. Each morning after reveille the order was bellowed out:

"Riiiight ., .face. , .double time. , .maaarch,"

and the entire command, colonel to private, was off on a two-mile run around camp, in step and in formation. In the afternoon there was either a routine run of six to eight miles or a seven-mile special up and down Mount Currahee. Once or twice a week "speed marches" of five miles in forty minutes were made, with full packs and all weapons--including mortars and machine guns. Throughout all training pushups were administered as mild punishments. A descriptive chant developed which was sung while running in formation:

"Every day we run up to the top of Currahee,

Fifty pushups after that's too goddamn much for me,"

Each trooper was required to qualify as 'expert' with his individual weapon, 'sharpshooter' with another, and 'marksman' with all crew-served weapons in his platoon. None of these were easy. For weapons qualification, battalions bivouacked at the snake-infested Camp Toccoa range. There was plenty of ammunition. Those who failed to make the required qualifications the first time refired until they succeeded, Each week those who met the requirements were allowed to come back to camp while the others kept at it. After several weeks, despite best efforts, a hard core of "bolos"* still remained. Eventually they managed to sneak back in more or less unnoticed. Colonel Walsh's marksmanship requirements, while highly desirable, were not always attainable.

| * The term "bolo" originated during the Philippine insurrection, when men who could not qualify with rifles were contemptuously told the only weapon they were fit to use was the "bolo" machete. |

On week nights "officer's school" was conducted for three hours after the evening meal. Classes were help in various subjects ranging from "the platoon in the attack" to rigging bundles for parachute drop. Field grade officers and senior captains were the instructors. After class the officers were free for what remained of the evening but still had to instruct the troops the next day. Most platoon leaders, almost as inexperienced as the troops they were instructing, managed to stay ahead only by cramming on field manuals long into the night.

Despite this harsh regimen -- or perhaps because of it -- most of the officers and men of the 517th were solidly behind Colonel Walsh. Young men tend to cynicism and like all Americans the often made flippant remarks, but inwardly they understood what he was trying to achieve. they were proud of themselves and the outfit and ready to follow wherever he might lead.

From the incoming manpower, a three-battalion regiment of 142 officers, 2 warrant officers, and 1,856 enlisted men had to be created. The Tables of Organization and Equipment for parachute units were restricted by the technology of the time. Everything had to be deliverable by the parachutes and aircraft then available. It was visualized that paratroops would land on or near their objectives and fight for only a few days before being relieved. Units were to be "lean and mean" with no non-fighters or administrative frills.

The rifle squads were the cutting edge of the sword. There were two per platoon, six per company, and eighteen in each battalion. Each rifle squad consisted of a squad leader, an assistant, a three-man machine gun team, and seven riflemen. Two such squads and a 60mm mortar squad made a rifle platoon, commanded by a lieutenant with an assistant platoon leader, a platoon sergeant, and a few runners.

From company through regiment the organization was "triangular." Three rifle platoons made a company, three companies a battalion, and three battalions a regiment. At battalion and regimental levels additional support was provided. The battalion headquarters company included 81mm mortar and machine gun platoons. At regiment there were headquarters and service companies.

To free company and battalion commanders from administrative chores, personnel, food service, and supply were centralized in Service Company. This looked good on paper but did not work out well in practice, because the commanders lost control of factors that affected morale. In the 517th, Supply Sergeants were released to companies and clerks found their way into orderly rooms, but Service Company operated battalion messes throughout the war. Anyone who has tried to feed 600 people at one sitting can imagine the result. Out of necessity the troopers normally subsisted on the individual C and K rations in the field. These were intended only for emergencies, but became the steady diet.

The regiment was authorized only enough vehicles to meet garrison administrative needs. This was acceptable in airborne operations, but in prolonged ground combat -- which was the case most of the time for the 517th -- the shortage of vehicles was a constant headache and source of hardship.

There were seldom any complaints over the Regiment's Medical Service. The Tables of Organization allowed eight Medical Corps officers, one dentist, and 69 enlisted men. These were divided into a Headquarters and three Battalion sections. The Headquarters section took care of supply, records, and reports, and tended the sick and injured of Headquarters and Service Companies.

Each Battalion section had two medical officers, seventeen men, and a jeep. This allowed two aid men to each rifle company, two litter teams, and a Battalion Aid Station. The jeep was rigged up as a platform for two litter cases. the Battalion Aid Stations were dressing stations and relay points for the evacuation of wounded, who were carried to Field Hospitals by Ambulance Collecting Companies.

Though understaffed and under-equipped, the Regiment's Medical service performed brilliantly throughout the war. On innumerable occasions lives were saved by evacuation and treatment under desperate conditions. The Medics were always well up front with the riflemen. Many men are alive today because they were there.

It wasn't all deadly serious. One night on returning from compass-course training, Major Boyle noticed a crowd of men gathered around the B Company supply room. He pushed his way through and found the B Company Supply Sergeant perched on a high counter. A large lion cub lay docilely on the floor .

It seemed that Captain Eldia Haire, deciding that his company needed a mascot, had persuaded the St. Louis Zoo to send the lion by way of helping the war effort. Although only a cub, the lion was big and potentially dangerous.

The mob scene was dispersed. Locked up in a hut of its own, the lion proceeded to reduce a pile of pillows and mattresses to a large stack of GI duck feathers. Colonel Walsh got wind of the affair but hesitated to take action. The feline might help morale, although he would have a hard time explaining to the authorities if anyone got hurt. For several weeks groups of B Company men were seen walking -- or being walked by -- the lion on the end of a long, strong chain.

A few weeks later the first Regimental "Prop Blast" party was held. As the ceremonies were winding up Major Boyle sensed that the supply of spirits was about to run out, and began to leave for the off-post "Hi-Dee-Ho" club. Several others joined him, including "Ike" Walton. All piled into Boyle's ancient Ford. Walton had never seen the lion, so at his urging they detoured by B Company. Colonel Walton then decided that it would be a great idea to bring the lion to the party. No one was going to disagree with the Regimental executive officer, so they pushed the feline into the back seat of the car and rolled off .

Cats do not like being awakened, particularly in the middle of the night; they also generally dislike automobiles. The lion perceived Boyle as the chief villain and tried to escape, taking several swipes at him. Medical attention was required.

Next morning Major Boyle arrived at the rifle range looking like the Sultan of Swat, his head swathed in a turban-like bandage with steel helmet perched on top. Colonel Walsh eyed him suspiciously.

"What happened to your head?"

"Sir, the lion got a little too playful last night."

That finished it as far as Colonel Walsh was concerned. In his words " ... I managed to get rid of the damned thing by convincing Jupe Lindsey that he ought to have it as a mascot ... " The lion was shipped out to join the unfortunate 515th Parachute Infantry at Fort Benning.

Regimental S-2 Captain Albin Dearing was a sophisticated and cosmopolitan man with literary and theatrical connections. On learning one day that the well-known comedian Bob Hope was scheduled for an appearance in Atlanta, Dearing asked Colonel Walsh for permission to try to get him to make a side trip to Camp Toccoa. To the great surprise of everyone except Dearing, Hope agreed, and a few days later a C47 carrying him and his troupe put down after dark at a tiny nearby airstrip.

Bob Hope was (and is) a quick study. His success is based in large part upon his ability to adapt to the idiosyncrasies of any particular audience. Enroute to the camp Colonel Walsh gave him a quick rundown on paratroopers and parachute training.

The entire regiment was assembled in the Post theatre. After being introduced with a not very original pun ("... I now present our last Hope. ..") Mr. Hope delighted his audience by pretending to struggle through an exaggerated pushup. The performance was brilliant. The troopers felt that if a celebrity like Bob Hope could take time to visit tiny Camp Toccoa, perhaps their efforts were being appreciated. In his own way Bob Hope contributed greatly to the war effort.

It had been planned to fill the Battalions in numerical sequence. By the end of April Major Boyle's 1st Battalion was almost complete. At the end of the following month Major Seitz' 2d Battalion was pretty well on its way. But in late June or early July, while Major Zais' 3d Battalion was still waiting for its first recruit, the flow of volunteers to Toccoa was suddenly turned off. It was announced that the 3d Battalion would be filled with Parachute School graduates who had already completed basic. Higher headquarters apparently felt that the 517th had rejected too many men and that the selection process was taking too long.

Part of the problem may have been faulty bookkeeping. Men en route to Toccoa were picked up as "assigned" to the 517th when they left the Induction stations*; men awaiting shipment out of Toccoa were also carried as "assigned" until they reached their new destinations.

| * Some never arrived. General Walsh likes to tell of how "... the Governor of one of our distinguished western States released 50 life prisoners on the condition that they volunteer for parachute duty, They were loaded on the railroad and haven't been heard of since ..." |

The Regiment had applied the medical standards prescribed by the War Department for parachute duty. Colonel Walsh had been allowed full discretion in all other areas. His Battalion commanders may have been over-selective, but hindsight is easy. The bottom line is that very few of the men selected ever let the outfit down. In late summer an advance detail staked out a claim at Camp Mackall and the Regiment moved to Fort Benning for parachute training.

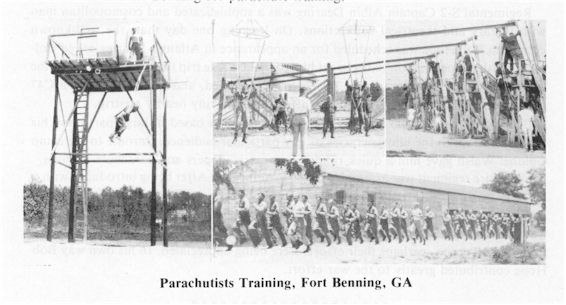

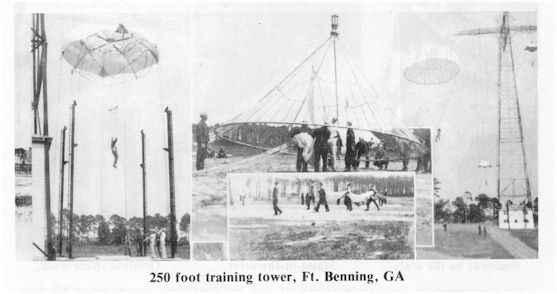

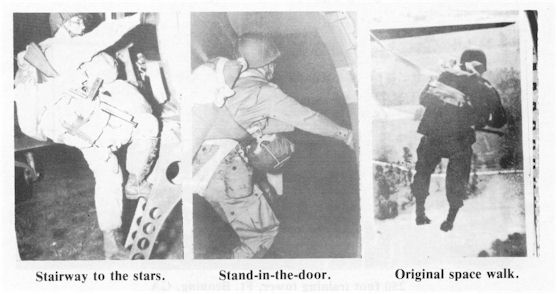

The Parachute School was a model of military efficiency in the highest sense of the term. Most of the School's physical plant was tucked away in a corner of Lawson Field, behind the airplane hangars. There were 34 foot "mock towers", similar to the one at Toccoa, and airplane mockups, "landing fall trainers", the "suspended harness", the "plumbers nightmare" and other instruments of torture. In the Main Post area were four 250 foot steel parachute towers, modeled after one that had been at the New York World's Fair of 1940.

The Parachute School Instructors were as fine a group of NCO's as any that has ever been assembled. The School had originally been cad red by the Test Platoon and the 501st Parachute Battalion, and continually added a few outstanding graduates of each class to its staff. Each Parachute School instructor was a rugged physical specimen with an air of authority and command that was envied by most officers. They established a tone and set a pattern of behavior that carried over into every American parachute unit.

The parachute course consisted of A, B, C, and D stages, each a week long. Physical conditioning was emphasized. The 250 foot towers were used in C stage, and D stage consisted of five live jumps.

The months of jogging, pushups, speed marches, running up and down Currahee, and all the rest paid off for the 517th troopers. They were more than ready for the worst the school could dish out. The School Instructors, accustomed to classes of men who had finished ordinary basic training, were astonished to find that the 517th men were in as good shape as they themselves were. Extra miles and pushups were piled on to find chinks in the 517th's armor, to no avail. As hard as they laid it on, the 517th troopers grinned and asked for more. It was finally tacitly conceded that there was no way the Instructors were going to get the 517th to cry "Uncle."

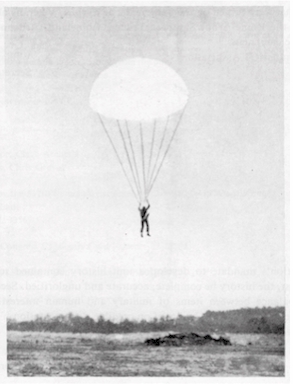

No paratrooper will ever forget the "Command Sequence." The red light at the exit door comes on. "GET READY. ..STAND UP. ..HOOK UP" ... the plane sways and bucks, and you are on your feet struggling to hook the snap fastener over the anchor cable ... "CHECK EQUIPMENT" ... a quick look at the parachute and webbing of the man in front ... "SOUND OFF FOR EQUIPMENT CHECK" ... "Fifteen OK" ... "Fourteen OK" ... and so on down the line. ..the plane's engines backfire and it slows down, almost stalling ... the green light flashes on ..."LET'S GO! ' , ... a sickening feeling in your lower gut, but you are determined to take those next few steps ... suddenly, silence and you are suspended in space until hit by a force of 4 or 5 G's ... overhead is a canopy of white, and all is serene until you realize that the ground is rushing up to meet you at fifteen miles per hour .

Afterward, a euphoric "high" that lasts several hours or days. ..or until the next Jump.

The 517th breezed through jump school with no washouts, setting a record that has endured to this day. School Commandant General Ridgely Gaither said that the 517th's battalions were without equal in discipline and effectiveness--which says a great deal for Colonel Walsh's selection and training methods. The 517th troopers were the first to wear the steel helmet in jump training; until then a modified football helmet had been used.

On completion of jump training the 1st and 2nd Battalions moved on to Mackall while the 3d remained at Benning to complete fill-up. Leaves were granted, and cities and towns rejoiced in the sight of jump wings and gleaming jump boots, whose proud owners had been allowed to stuff their pants into them for the first time.

Camp Mackall was not much different from Toccoa but bigger, on level ground. Everyone was quartered in the same one-story, uninsulated "hutments" heated with coal stoves, and the same drab, all-male existence went on. Passes were allowed, but after a few visits to the local small towns most troopers decided they might just as well stay in camp. The 17th Airborne was big on athletics, and the 517th shook it up a little by fielding football and boxing teams that won the Division championships.

One day an inspection team from Headquarters Army Ground Forces arrived at Camp Mackall to test the Regiment's physical fitness. Using more-or-less scientific statistical sampling methods, men and units were selected and put through their paces. Individuals took the Physical Fitness Test, consisting of pullups, pushups, and other weird calisthenics, done against time. Platoons and companies were chosen to run and march, with and without equipment, for various distances.

When all was done the results were analyzed and announced. The 517th had taken first, second, and third place in all tests and events, scoring higher than any unit tested before or since.

Undeniably, the 517th was a regiment of jocks.

Through the fall the regiment conducted unit training--tactical exercises for the squad, platoon, company, and battalion. Effort was made to conclude each phase of training with a parachute jump. Sometimes jumps had to be cancelled because of weather or lack of airplanes, but men and units averaged one per month.

In one exercise at Maxton Air Base Catholic Chaplain Father Alfred Guenette distinguished himself by jumping twice but only landing once. On the first jump the wire-and-canvas "pack tray" of his parachute snagged on a projection on the airplane's door. The priest hung outside the plane, beating helplessly against the fuselage, until the air crew noticed something wrong and dragged him back inside. Father Guenette bravely drew another parachute and tried again, this time successfully.

The newly-established Airborne Center at Camp Mackall was now prescribing training doctrine. One of its requirements for parachute units was a 300-mile flight, followed by a night jump and a three-day ground exercise, with all supply by air. The 517th took its turn in this operation in January, working with the same troop carrier formations that later were to drop the 82nd and 101st in Normandy, and the 517th itself in Southern France. The exercise was successful and unremarkable, except that due to an error in altimeter settings C Company dropped at an altitude of 200 feet. Fortunately there were no malfunctions. A day after the landing the weather turned cold, with sleet, snow and freezing rain. Men became walking icicles and found that the standard jump suit and boots were not very practical for cold-weather wear.

In February the regiment moved to Tennessee to take part in maneuvers being conducted by Headquarters Second Army. The' 'Tennessee Maneuvers' , were a sort of little practice war that went on year around. Divisions and regiments came and went, being assigned to either the "red" or the "blue" forces. Participation in the Tennessee maneuvers was supposed to be the final test before a unit could be pronounced combat-ready.

Without the stimulus of live fire and with inadequate umpire control the maneuvers were ludicrous. Units marched day and night through rain and mud. When opposing forces did meet, a sort of "Pickett's Charge" by one side or the other usually resulted. Malaria discipline was tested by wearing mosquito headnets in the winter cold and rain. On one occasion the regiment marched for 24 consecutive hours, covering over fifty miles.

One cold day in March when all were

shivering and knee-deep in mud, it was announced that the parachute elements of

the 17th Airborne Division were being pulled out for overseas shipment as the

517th Regimental Combat Team. This news was received with greater elation than

the end of the war a year later. If there is a special hell reserved for

soldiers who have sinned, it must be something like the Tennessee maneuvers.

One cold day in March when all were

shivering and knee-deep in mud, it was announced that the parachute elements of

the 17th Airborne Division were being pulled out for overseas shipment as the

517th Regimental Combat Team. This news was received with greater elation than

the end of the war a year later. If there is a special hell reserved for

soldiers who have sinned, it must be something like the Tennessee maneuvers.

So, from the mud of Tennessee, the 517th Parachute Regimental Combat Team emerged. The parachute units were hastily shipped back to Camp Mackall to prepare for overseas movement, leaving the glider-riders of the 17th Airborne to their own devices.

The 460th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion, with an authorized strength of 39 officers and 534 enlisted men, consisted of a Headquarters and four firing Batteries, each with four 75mm pack howitzers. The 75 had been originally developed for animal transport in mountain warfare. It was a relatively light and versatile artillery piece which threw a 13.9 pound shell for a maximum range of 9,650 yards.* The 75 broke down into seven pieces for parachute drop. A "ground control pattern" connected the bundles in descent, preventing the pieces from floating off in seven different directions.

| * M41A1 shell. |

Two weeks before embarkation the Battalion commander and staff of the 460th were relieved. Lt Col Raymond L. Cato, USMA '36, and eight officers of the 466th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion were assigned in their place.

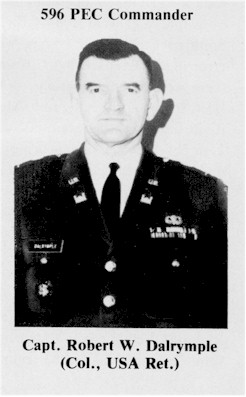

Company

C, 139th Airborne Engineer Battalion, was redesignated the 596th

Airborne Engineer Company. The 596th had a company headquarters and

three platoons, with an authorized strength of 8 officers and 137

enlisted men. It was commanded by Captain Robert Dalrymple. He and his

officers had been hand-picked, and had attended a 30-day course at Fort

Belvoir, Virginia, prior to the Company's activation.

Company

C, 139th Airborne Engineer Battalion, was redesignated the 596th

Airborne Engineer Company. The 596th had a company headquarters and

three platoons, with an authorized strength of 8 officers and 137

enlisted men. It was commanded by Captain Robert Dalrymple. He and his

officers had been hand-picked, and had attended a 30-day course at Fort

Belvoir, Virginia, prior to the Company's activation.

The Engineers were lightly armed and equipped, but highly trained in their missions of construction and destruction. This training -- particularly in the removal of mines and booby-traps--was to stand them in good stead on the battlefields of Europe.

Most of the enlisted artillerymen and engineers shared a common background with the 517th Infantrymen, having entered the Army and gone through the Camp Toccoa screening process at about the same time. The 460th and 596th became integral parts of the 517th Parachute Regimental Combat Team, and provided it loyal and enthusiastic support throughout its career.

The 517th RCT received no special augmentation to allow it to function as a separate unit. It was expected to operate as a small Division, although it lacked many of the specialized services and agencies available to a larger force. It was, in fact, "standing alone" and would have to make do with what it had.

On return to Camp Mackall all efforts were concentrated on preparation for overseas movement. Wills and Powers of Attorney were made out, leaves granted, and shots taken for virtually every communicable disease known to man. Crew-served weapons, artillery, and vehicles were cosmolined, crated, and readied for shipment. When all was done most companies and batteries were left with little more than individual weapons, the First Sergeant's records chest, and a broom.

In the midst of this activity the word spread one day that Colonel Walsh had been relieved. I t was a real shock to the 517th troopers. He had put all he had into making the regiment a first-class fighting force with an esprit and elan second to none. Unknown to most, he had frequently gone to bat with higher headquarters for his officers and men. On at least one occasion he had offered to quit unless charges he felt were unjust were dropped. It was a personal tragedy. The majority were angry and felt that he had been sandbagged.

But in the Army as elsewhere life must go on. Colonel Walsh's successor was Lt. Colonel Rupert D. Graves, USMA '24, who came from command of the 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion. A somewhat older man in his early 40's, Colonel Graves was cool, calm, unassuming, and professional. Like all new commanders he was closely watched while the troops, treading carefully and with great circumspection, tried to take his measure. Graves quickly proved to be likeable and unflappable, and before long things settled back to normalcy.

In early May the RCT components staged through Camp Patrick Henry, near Newport News, Virginia. The troopers milled about more or less aimlessly for ten days, making the acquaintance of some lovely members of a W AC contingent and an unlovely shipment of Air Corps replacement officers who were to be their shipboard companions. Some raucous paratroopers tried to get one of the aviators to give them flying lessons from the second-floor balcony of a service club, without success.

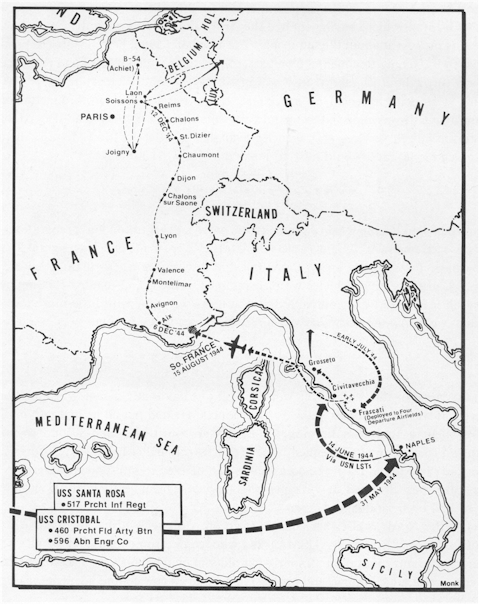

On May 17th the troopers climbed the gangplanks for their great adventure. The 517th boarded the former Grace liner Santa Rosa* with the WACs and aviators, while the 460th and 596th loaded onto the Panama Canal ship Cristobal. As the Santa Rosa pulled away from the dock Chief Warrant officer Everett Schofield, Regimental Personnel officer, was at the rail with a few others. Schofield, the oldest man in the regiment and a veteran of the First World War, found himself reenacting scenes that had taken place twenty-six years before. He must have had a sense of "deja vu." Indicating the troopers swarming allover the ship, the Chief said, "Take a good look. This outfit'll never be the same again."

| * By an extremely odd coincidence, the shrine of the actual Ste Roseline was going to become familiar to them all within a few months. |

Chapter II

Arrividerci Roma

In late afternoon Santa Rosa and Cristobal sailed down the James River. At Hampton Roads the transports were joined by a Navy destroyer and the little convoy headed out into the open Atlantic. The odyssey of the 517th RCT had begun. Although the ships were overcrowded and had few amenities it was a pleasant trip under sunny skies. The destination was unknown but the majority felt it would be England. It was common knowledge that the invasion of Europe would soon begin and parachute troops would be needed. Few gave any thought to the possibility of submarine or air attack; the war was still something to read about in the newspapers.

Duty rosters for the shipboard housekeeping chores had been posted on bulletin boards. An hour after embarkation Lieutenant John (Tiger) Rohr of B company discovered, to his horror, that he had been detailed as an assistant to the troop mess. His job was to stand with a thermometer beside a hot water tank and make sure that the troops washed their mess gear after every meal. This was a tedious chore for a man of spirit. Rohr endured the indignity for almost an entire day, and even got a little fun out of it by growling at the WAC's, "Wash that mess kit, soldier. Ya wanna get the GI's?" But it soon became tiresome, and Tiger decided to exercise a little imagination. Somehow he found 'a list of all officers aboard -- including the Air Corps contingent -- and gained access to the ship's PA system.

Selecting the first aviator on the list, he announced, "Now hear this ... Lieutenant Ashe, report to the troop mess. Lieutenant Ashe ..." Tiger then dropped the mike and raced below, arriving at the troop mess just before the 19-year old Ashe. With all the authority of a first lieutenant speaking to a second, Tiger explained that "I am Lieutenant Rohr, Chief Mess Officer. You have been detailed as one of my assistants. Your job will be to make sure that the water is kept at a boil and that the troops wash their mess gear after every meal ... Are there any questions? I'll be around to check up from time to time, and if you need me in the meantime I'll be in my stateroom ..."

The guileless Ashe performed the duty for the rest of the voyage. Rohr proved to be a poor supervisor; he never went back.

The presence of 200 young ladies on board Santa Rosa naturally drew the 2,000 males like flies to honey. Measures were taken to prevent over-fraternization, but no amount of regulation has ever been able to alter human behavior. After dark blackout curtains were drawn and no one was allowed on deck, but Santa Rosa was a big ship and it was impossible to police all the gangways and passages. One young individual who considered himself quite a lady's man boasted of his prowess until his fellow-officers could no longer endure it. They set up a "sting" operation, in which the victim received a series of notes from a secret admirer. After a prolonged courtship a meeting was arranged. The unfortunate Casanova discovered that his lover was a well-padded and disguised brother officer, and the tryst was suddenly broken up by the arrival of his friends.

One dark night the ships slipped through the Straits of Gibraltar and it became obvious that the destination was Italy. After hugging the coast of Africa for a few days the transports headed northeast. Off Sardinia there was a little excitement abroad Santa Rosa when it came near a floating mine. A crew member got a rifle, but dared not fire because the mine was only a few yards from the ship's side. While the spectators held their breath waiting for an explosion the ship sailed on, leaving the mine bobbing wickedly in its wake.

This idyll came to an end when Santa Rosa and Cristobal docked at Naples on May 31st. The troopers filed down gangplanks into waiting railroad cars and were carried to a staging area in the Neapolitan suburb of Bagnoli. Enroute Colonel Graves was handed an order directing the RCT to take part in the attack from Valmontone to Rome next day. The 517th was ready to go, but since crew-served weapons, artillery, and vehicles had been loaded separately it would have to be with only rifles. After this was pointed out the order was cancelled and the RCT moved on to "The Crater ." The Crater was the bed of a long-extinct volcano that was rumored to have been the private hunting reserve of Neapolitan royalty (such as that may have been). It was a flat, circular area surrounded by the volcano's rim. Whatever hunting had been done there had probably ceased a hundred years before. The troopers set up a tent camp and settled down to wait for weapons and vehicles to arrive.

It turned out to be a two weeks' wait. Activities were varied. A lucky few went on pass to Naples. A team from the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion put on an edifying demonstration of German weapons. The troopers found the high rates of fire of the Ma 42 and MP 40 "burp gun" highly impressive. Ordnance experts assured them that at those rates of fire the weapons were bound to be inaccurate, but many skeptics decided that the Ordnance were not the ones who were going to be shot at. The rifle companies were assigned 10% overstrengths to replace casualties before they occurred -- a depressing thought. News was received of the fall of Rome and the invasion of Normandy. It seemed as though the 517th was going to spend the rest of the war in an ancient lava pit while history passed it by.

Gradually weapons and vehicles arrived. Cosmoline was removed and the equipment put back into operation. On June 14th the outfit struck tents, stowed away extra gear, and moved to a beach at Naples to wait for LST's to carry it to Anzio.

The Navy had been running a sort of shuttle-bus service to Anzio since the landings in January. At about noon an LST flotilla pulled in to shore. The crews disappeared into the "Alligator Club" near the docks. After several hours they emerged and the RCT loaded, three ships per battalion. The troopers filed aboard, were handed C-rations, and told to make themselves comfortable anywhere they could find space on the crowded decks. In the evening the ships raised ramps, backed out into the channel, and headed north.

During the night the RCT's destination was changed. It had been scheduled to land at Anzio, but the Fifth Army was now far beyond Rome and had uncovered several little fishing ports along the coast. At midday the LST's put in at bomb-wracked Civittavecchia, dropped ramps, and the troops marched off to bivouac several miles inland. Although the area had been cleared of Germans, they had left some souvenirs behind. A newly-assigned 3/4 ton truck went up in a column of black smoke, the victim of a Tellermine.

The RCT was attached to Major General Fred L. Walker's 36th Infantry Division, which under IV Corps was operating on the left of Fifth Army. A long truck ride and a short foot march on the 17th brought the units south of Grosseto. The troopers dug "wistful foxholes" among the rocks while the 460th contacted 36th Division Artillery and moved into firing positions.

Field Marshal Albert Kesselring's forces were in full retreat. An Allied offensive that began in April to draw troops away from Normandy had finally taken Cassino. Forces advancing from the south had linked up with those at Anzio and captured , Rome. The German Army had been decisively defeated and was moving to a new line above the Arno River .

The Italian terrain was ideal for defense. The Appenines run down the spine of the peninsula; numerous spurs extending east and west formed cross-compartments over which the Allies had to advance. Any hilltop provided good observation and fields of fire. Villages dating from medieval times were perched on hills, and very little effort was required to convert them into fortresses.

The 36th Division was sometimes called "The Texas Army", because it had been formed around National Guard units from that State. Since landing at Salerno in September of 1943 the Division had developed a highly professional attitude toward the war. There was no rush. The Germans had been here yesterday, were here today, and would still be here tomorrow. In contrast the 517th was green, eager, and anxious to prove itself. Colonel Graves was handed an overlay marked with zones, objectives, and phase lines. The regiment was to join the Division's advance north from Grosseto next day.

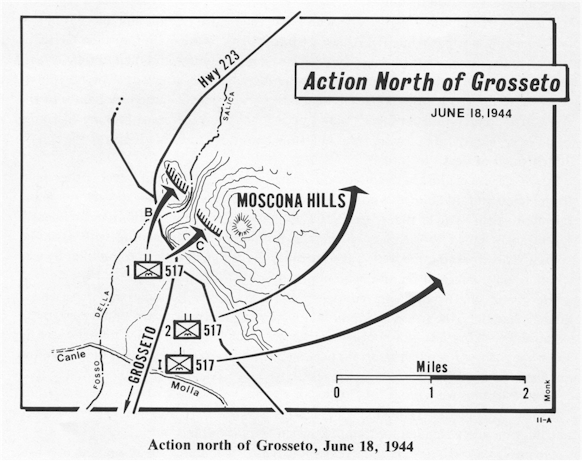

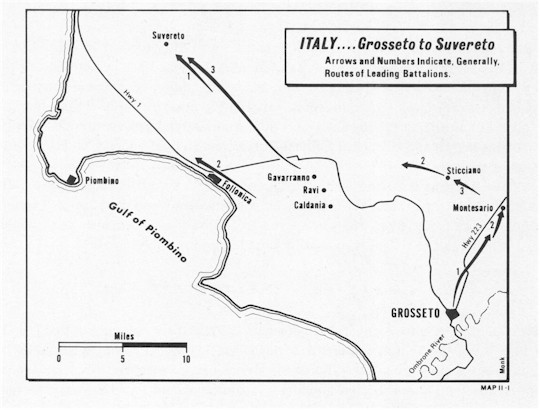

Grosseto had been given up by the Germans without a fight. The town lies in a flood plain formed by the Ombrone River. Criss-crossed by irrigation canals, the plain is ten miles wide at the coast and narrows to three miles inland. Leading north from Grosseto are Highway 223 to Siena, inland, and Highway 1 to Follonica on the coast. North of the Ombrone plain a ridge titled the "Moscona Hills" rises to 300 meters at the point where it is crossed by Highway 223.

At daylight on June 18th the rifle battalions filed through Grosseto heading northeast on Highway 223. The order of march was 1st, Regimental Command Group, and 2nd and 3rd Battalions. Combat loads of ammunition had been issued. Riflemen were festooned with ammunition bandoleers and grenades. Machine gun crews carried 1,000 rounds apiece. Rain early in the morning had tapered off into a light drizzle. Most men wore raincoats or ponchos.

Mechanized cavalry had reportedly been through the area and found it clear, but the leading company of Major Boyle's 1st Battalion ran into a storm of machine gun fire as it entered the Moscona Hills. The troopers fanned out, took cover, and returned fire. Sergeant Andrew Murphy of B Company became the regiment's first fatality, hit by a sniper while directing his squad's 60mm mortar fire. In the lead of the column, Major Boyle had been well forward with his Command Group and was pinned down. Battalion executive Herbert Bowlby came up from the rear to direct C Company to bring down fire on the enemy from a hill to the right.

The Germans held a group of farm buildings in a small valley. With a platoon of B attached, C Company moved to the ridge overlooking the farm and opened fire. Little could be seen. Enemy machinegun fire clipped leaves from a hedgerow; within a few minutes ten C Company men were hit. German mortars went into action. Fortunately, the freshly-plowed ground was still soggy from the morning rain. Most of the mortar shell fragments went straight up, but two more men were hit. Without waiting for orders, three men went down into a ravine to fight their own personal war. In four trips they killed several Germans, captured and turned a mortar against the enemy, and took nineteen prisoners.*

| * Staff Sergeant Wilford Anderson and PFC Nolan Powell were awarded the DSC for this action. |

Colonel Graves had received no word from the 1st Battalion, but its predicament was obvious. He committed Lt. Col. Dick Seitz' 2nd Battalion to envelop the enemy from the right, and sent I Company from the 3rd Battalion to protect the eastern flank.

Battalion 81mm mortars and 460th guns opened up. Under this fire and with pressure on their front and flank, the Germans pulled out. They left behind over a hundred prisoners and considerable number of dead and wounded.

Coming forward to survey the scene, Colonel Graves found the 1st Battalion preparing the wounded and prisoners for evacuation. At the Aid Station Captain Ben Sullivan was administering blood plasma to Lieutenant Howard Bacon of B Company, who had been shot through the chest and lungs. He looked as though he was done for , but under Sullivan's care survived.*

| * Bacon fully recovered, returned to duty, and led a rifle platoon through the rest of the war. |

In the early afternoon the advance was resumed. At twilight the Battalions took up rough perimeters and halted for the night. On the east I Company had become trapped in a minefield under machine gun fire. It was extricated after dark. The troopers were startled to find that the "German" force had been elements of the 162nd Turcoman Division,* recruited from Moslem minorities in the Soviet Union. Although the 517th troopers had not really expected all Germans to be blond supermen eight feet tall, neither had they expected these scruffy, undersized Mongolian types . The enemy's tactics were also baffling. In a delaying action it is standard practice to open fire at long range, forcing the enemy to deploy prematurely. The Turcomen had not read the book and allowed the 517th to get almost on top of them, which proved their undoing.

| * The Army "Order of Battle Handbook" later listed the 162nd Turcoman Division as having been 'virtually destroyed' in Italy in June. After the war the remnants of the Division were returned to Soviet Russia, where it can be safely assumed that the destruction was completed. |

In its all-important first day of combat the regiment suffered 40 to 50 casualties but inflicted several times that number upon the enemy. Far more important, the outfit had experienced the sights and sounds of combat and learned that it could fight and win.

The next seven days were spent in almost continuous movement. The Germans tried to make an orderly withdrawal while the Americans pressed them hard. It was a "pursuit" situation, but a pursuit that went only as fast as men could march up and down the endless succession of hills.

All the Armies in Italy -- the American Fifth, the British Eighth, and the Germans -- were moving north. While the Allies stuck primarily to the main roads the Germans moved in the same direction on secondary lanes, pausing now and then to fight a rear-guard action. Both sides frequently became lost and intermingled. The hot, dusty roads were littered with wrecked German tanks and trucks -- largely casualties of the Air Corps "Operation Strangle"* -- and occasional dead Germans looking like limp bundles of bloody rags. Under the hot June sun it did not take long for the sickly-rotten smell of death to spread.

| * "Strangle" was the code word for the Air Corps interdiction program. |

It was easy to get lost in the mountains, where each hill looked like every other one. Companies and Battalions would halt and the officers begin to spread out maps (always discouraging to the troops: "Christ, they've got us lost again.") Frequently the infantry called for artillery to mark a prominent terrain feature with a smoke round. This worked quite well, but sometimes the requesting party found that he was standing on the terrain feature being marked .

Mules and "partizanos" played their parts. Lacking pack saddles and experienced animals handlers, the troopers found that pack mule transport wasn't all it was cracked up to be. After a few discouraging experiences in which the balky animals were hit by artillery fire or broke legs on slippery slopes, most units gave up on the mules and the loads returned to the trooper's backs.

The partizanos were fierce-looking locals wearing red scarves who had been hired by 8-2 to serve as guides. They knew their areas well but were over-inclined to socialize and, not unwisely, tended to disappear when a fight began.

On one occasion a rifle battalion emerging from a wood after an all-night march was met by a swarm of Germans trying to surrender. The troopers were in too much of a hurry to bother, and told the enemy to go surrender somewhere else. The Germans were crestfallen at this undramatic ending to their Wehrmacht careers. They had expected to at least be granted the dignity of surrender.

For the 460th the period was a continuous, 24-hour a day operation, a typical Field Artillery moving situation. Gun batteries continually leap-frogged each other; usually two batteries were in position while the other two were moving forward. When movement slowed all four were in position. The Fire Direction Center operated in two echelons, with one always in position and functioning. The 36th Division Artillery normally kept telephone lines into the FDC, enabling the 460th to call for fire from any Divisional unit within range.

In the RCT's brief engagement in Italy the principal chore of the 596th Engineers was road reconnaissance and mine-sweeping. In one reconnaissance Lieutenant George Flannery and two second platoon men ran into a German ambush and were killed.

On June 19th the 2nd Battalion captured the hilltop village of Montesario. On left the 3rd Battalion moved through Montepescali against light resistance, going on to take Sticciano with 14 prisoners. On the west along Highway 1 36th Division troops took Gavaranno, Ravi, and Caldania.

The RCT bivouacked overnight June 22/23 on a ridgeline south of Gavarrano. There was public bathhouse in the village and many decided to take advantage of it. Mess and supply trucks moving on the ridgeline drew German artillery fire. Several troopers dived into the bath, clothes and all.

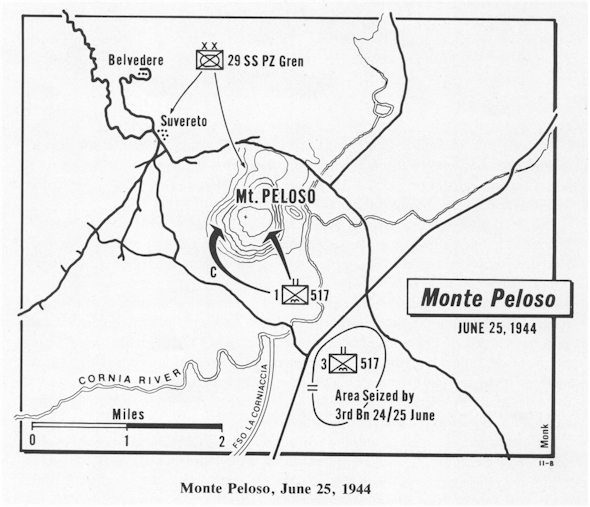

Next morning the RCT moved across the Piombino Valley and closed into an assembly area behind the 142nd Infantry. On June 24th the 2nd Battalion entered the eastern outskirts of Follonica under heavy artillery and "Nebelwerfer" fire. During the night of June 24/25 the 3rd Battalion made a long infiltration, emerging next morning on high ground overlooking the dry stream bed of the Cornia River. At 0800 the 1st Battalion passed through the 3rd to seize Monte Peloso, dominating a broad valley with the town of Suvereto about a mile north of the far side.

The attack was preceded by a heavy artillery barrage fired by 36th Division Artillery under 460th direction. Moving in column along the dry stream bed, 1st Battalion met minor delays as skirmishers with "burp guns" fought to slow the advance. Six hundred yards short of the objective Major Boyle called his company commanders forward for orders. As they began to assemble enemy 81mm mortar fire came in, wounding Boyle and several others.

Under cover of a smoke screen laid down by "Pop" Moreland's 81mm Mortar Platoon, one company moved west in a shallow envelopment to the left. PFC Carl Salmon silenced a machine gun with rifle fire, and the troopers rushed. the hill. While they were reorganizing an enemy motorcycle messenger arrived, took a horrified look, and raced away.

The enemy force had been a detachment of the 29th SS Panzer Grenadier Division, an altogether different breed than the Turcomen. None surrendered, although a badly wounded officer, incapable of further resistance, was captured and died a few hours later.

The remainder of the Battalion came forward and the position was consolidated. Major Boyle finally allowed himself to be evacuated, and executive officer Herbert Bowlby took command.

Enemy artillery fire continued heavy on Monte Peloso through the night. A haystack on the crest had caught fire during the afternoon. After dark it became an aiming point for the German artillery. At 0400 word was phoned down that "Daddy is here." No one had any idea what that was supposed to mean, but it became clear at daylight when the 3rd Battalion of the 442nd (Nisei) Combat Team moved in to take over. The 1st Battalion left the hill, formed up, and filed to the rear to join the balance of the RCT .

While the 1st Battalion had been taking Monte Peloso, Colonel Graves had been studying the terrain to the north. It was ideal for defense, with steep hills overlooking broad, open fields. In the distance he saw Tiger tanks moving around. Graves estimated that there would also be minefields to contend with. The Colonel was planning a night attack to Suvereto, and breathed a sigh of relief when he heard that the 442nd was to pass through the 517th in the morning.

The 517th went into IV Corps reserve and remained in that status until early July . While the troopers rested and awaited further commitment, the final steps toward a great decision were being taken.

The 517th had been sent to Italy in response to a Seventh Army request for airborne troops for ANVIL, the invasion of Southern France. ANVIL bad been agreed upon by the Allies at the Tehran conference in 1943, as a secondary attack to draw German forces away from OVERLORD, the main landing. In early planning it had been found that there were not enough landing craft for two simultaneous landings. ANVIL had been postponed until after OVERLORD, but planning and preparations for it had continued.

Now, with the Allies firmly established in northern France, ANVIL preparations were almost complete. Troops had been withdrawn from the line (including 517) and air and naval forces were assembling. All that was needed was a firm date and a go-ahead. But at this point, with the time for a final decision at hand, the British had second thoughts.

Since OVERLORD had succeeded they saw no need for a secondary attack in France; better, they felt, to use the ANVIL forces in Italy or elsewhere in the Mediterranean.

To the Americans Italy and the Mediterranean were sideshows. In their view all available forces should join the main battle in Northern Europe as soon as possible. General Eisenhower urged that ANVIL be executed on August 15th, stressing his need for the port of Marseilles. Roosevelt firmly backed Eisenhower and pressed Churchill to agree.

The British finally conceded, in reluctant recognition of the fact that the bulk of the combat forces were now American. On July 2nd the Combined Chiefs of Staff issued a directive to the CINC Mediterranean to go ahead with ANVIL (renamed DRAGOON) on 15 August.

As a byproduct of this directive the 517th RCT was released from IV Corps and moved to join the First Airborne Task Force in the Rome area.

Blissfully unaware of this high-level debate, the 517th settled in to enjoy life in bivouacs west of Frascati. Rome was eleven miles away and passes were liberal; the immediate mission was rest, recuperation, and rehabilitation of men and equipment.

Combat losses had been relatively low during the brief period in action, but still totaled 129, including 17 killed. On July 9th memorial services were presided over by Chaplains Brown and Guenette. Colonel Graves made a brief address, and the troops marched thoughtfully off.

Almost everyone came down with the "Roman trots", a short-lasting but distressful form of dysentery. The epidemic ran its course -- literally -- by mid-July. Training resumed but was not taken over-seriously; a great deal of time was spent marching to Lake Albano and back, enjoying a swim in the interim.

Headquarters Seventh Army had remained in Sicily after the conquest of that island in 1943. After the Tehran conference it was given the task of planning the ANVIL assault. A planning group called Force 163 was set up in Algiers and developed a concept calling for a three-division amphibian/airborne assault to seize Marseilles, advance up the Rhone Valley, and join the forces in northern France.

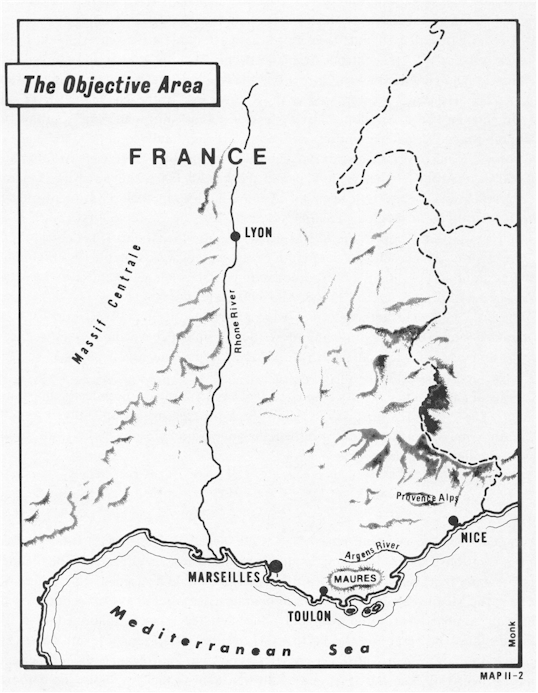

There was no "soft underbelly" in southern France. Dominating the area were the Central Massif, west of the Rhone; the Maures Massif, rising abruptly from the sea at Toulon and extending east to the Gulf of Frejus; and the Provence Alps, north and east of the Maures. Corridors were formed by the Rhone flowing south to Marseilles and the Argens flowing east to the Gulf of Frejus.

German strength, though not as powerful as in Normandy, was still formidable. Minefields, obstacles, and anti-airborne devices had been sown on beaches and airborne landing areas, and heavy artillery was em placed in well-camouflaged bunkers. At Toulon casemated 340mm guns from the battleship La Provence, put in by the French prior to WW II, controlled the approaches both to Toulon and Marseilles.

The German Nineteenth Army was along the Mediterranean coast. Four Divisions and a Corps Headquarters were west of the Rhone. East of the Rhone the LXII Corps at Draguignan had a Division each at Marseilles and Toulon and one southwest of Cannes. Many German formations were understrength, underequipped, and made up of non-Germanic "volunteers". But regardless of quality, there were an estimated 30,000 enemy troops in the assault area and another 200,000 within a few day's march.

Marseilles was the basic DRAGOON objective but its approaches were controlled by the fortifications at Toulon. Toulon would have to be captured first. Since direct assault was virtually impossible, it was decided to use the Argens River corridor as a "back door". The beaches at the mouth of the Argens were suitable for amphibious landings, and level ground for airborne landings was available inland near Le Muy. West of Le Muy exits led to Toulon, Marseilles, and the Rhone.

The 3rd, 36th, and 45th Divisions were placed on the tentative troop list. All veterans of amphibious landings and of extended combat, they would comprise the VI Corps under Major General Lucian K. Truscott, a brilliant cavalry officer who had directed the breakout from Anzio.

Political and military factors mandated that French units be used to the maximum extent. The French II Corps was to follow the Americans ashore on D plus 1, and the , Seventh Army commander promised them the honor and responsibility of capturing Marseilles and Toulon.

Planning for the airborne phase of ANVIL began in February, 1944, and went through various changes involving landing areas, missions, and forces. The planners decided early that an airborne force of Division size would be needed. Since there was none in the Mediterranean, a force of comparable size would have to be improvised. Units in combat were withdrawn and additional forces were requested from the United States. In response, the 517th RCT and the 551st Parachute and 550th Airborne Battalions were provided. The 517th was put into line to gain combat experience under Fifth Army, and the 551st and 550th were sent to Sicily to assist the Airborne Training Center. Other units in Italy were designated "gliderborne" to be trained by the 550th and the Airborne Training Center.

Major General Robert T. Frederick, who had made an outstanding reputation as commander of the First Special Service Force, was chosen to command the "Seventh Army Provisional Airborne Division" (later renamed the First Airborne Task Force.) To complete his staff thirty-six officers were flown overseas from Camp Mackall.

By early July the concentration of the airborne force in the Rome area was almost complete. The 517th was at Frascati, the 551st and 550th had arrived from Sicily, and training of the "gliderborne" units was in progress. Two additional troop carrier wings totaling 413 aircraft were enroute from England to become part of the "Provisional Troop Carrier Air Division" under Major General Paul L. Williams.

Generals Frederick and Williams established their headquarters at Lido di Roma and reviewed earlier ANVIL planning. They found the plans limited in scope and vague in detail. Insufficient transport planes and gliders had been requisitioned; selection of drop zones and glider landing areas had been made without proper assessment of terrain, mission, and troop capabilities. A new plan was developed, submitted to Seventh Army, and approved.

On July 18th the 517th RCT was formally assigned by Seventh Army to the First Airborne Task Force. However, Colonel Graves and his staff had been involved in DRAGOON planning for some time. In briefings at the Task Force Headquarters it had been revealed that:

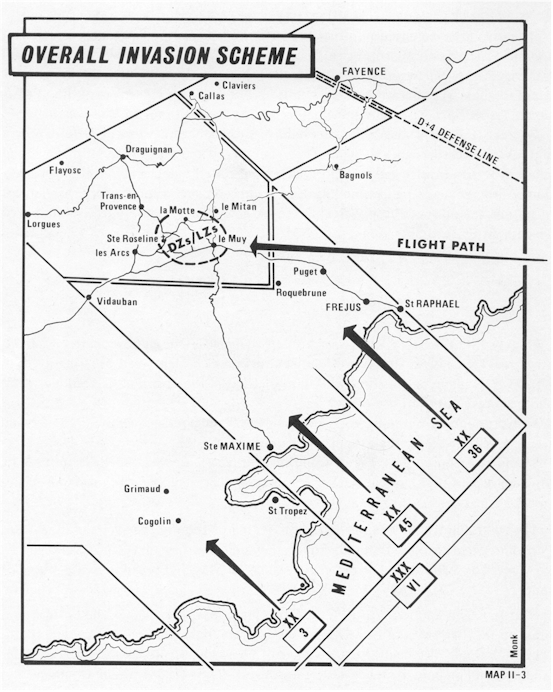

VI Corps, under Seventh Army, would assault the southern coast of France and secure a beachhead for the assault and capture of Toulon.

The First Airborne Task Force would make a parachute and glider assault near Le Muy, seize and hold critical terrain features, and prevent the movement of enemy forces against the beachhead.

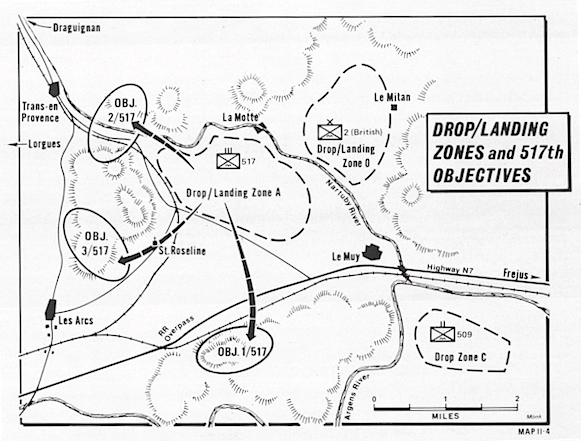

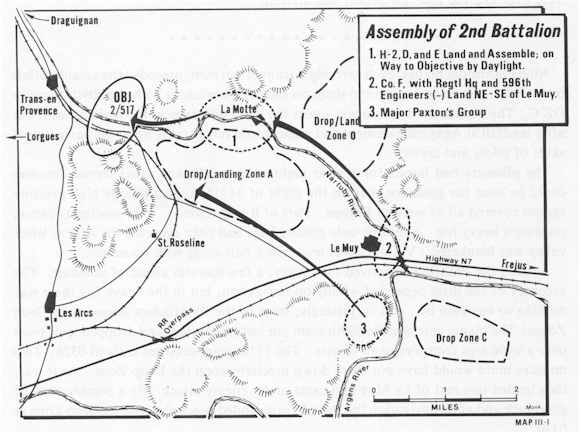

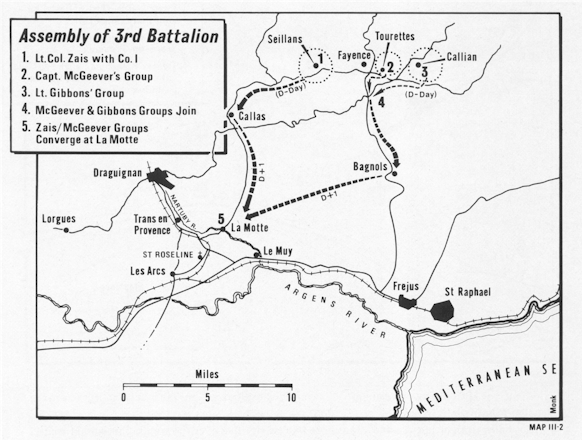

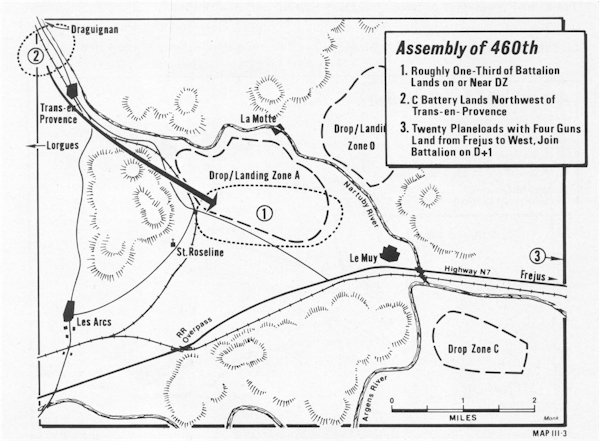

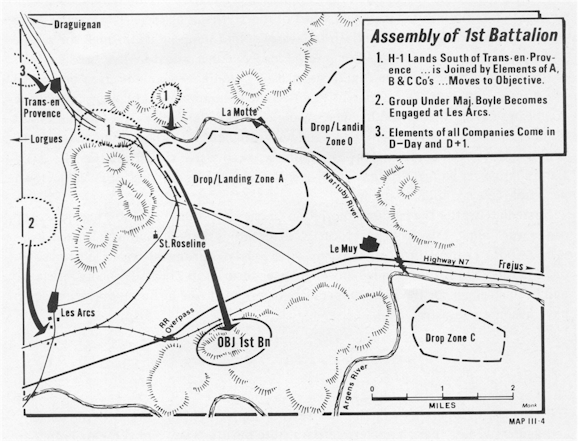

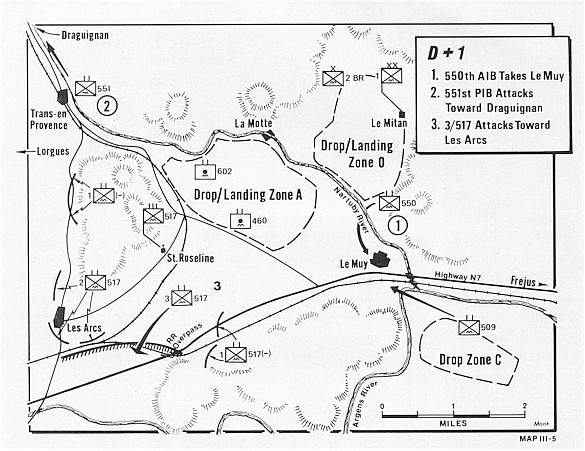

The 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion, with a platoon of the 596th and the 463rd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion attached, would land first on DZ "C" southeast of Le Muy. The 509th would seize terrain east of Le Muy and prepare to attack east or south.

Next in would be the 517th RCT, less one platoon of the 596th. The 517th would jump on DZ "A", west of Le Muy, and seize terrain to the northwest, west, and south. The RCT would also neutralize the village of La Motte, secure the DZ for later glider " landings, and prepare to attack west or northwest. The 442nd Antitank Company and Company D, 83rd Chemical Battalion, would be attached to the 517th after landing by glider.

The British 2nd parachute Brigade would jump last on DZ "O", northwest of Le Muy. The British were to seize Le Mitan, secure the DZ for later glider landings, and capture Le Muy before dark.

Task Force Headquarters and artillery of the British Brigade were scheduled to land by glider on DZ O at 0800. Reinforcing parachute and glider landings would begin at 1800, with the 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion to jump on DZ A and the 550th Airborne Infantry Battalion to land by glider on DZ/LZ O. The 551st was to relieve elements of the 517th in the northwest and the 550th would go into Task Force reserve. other supporting artillery and service units would then land by glider on both LZ's A and O.

H-Hour and D-Day were tentatively set for 0800, 15 August. The parachute assault was to begin before daylight and would be preceded by Pathfinder Teams, on all Drop Zones an hour earlier.

Colonel Graves and his planners went to work. Pathfinder teams of one officer and nine men from each battalion were sent to Marcigliana for training by Air Force experts and OVERLORD veterans. Service Company ran truck convoys to pick up three thousand parachutes at Naples, taking over Mussolini's "Science Building" near Rome for the parachute packing operation.

The 517th RCT had been allotted 180 C-47 aircraft in four serials * of 45 each, based at departure airfields at Ombrone, Orbetello, Montalto, and Canino. Now came the problem of how to best organize for the parachute landing.

| * "Serial" A formation consisting of several flights of aircraft, separated from other serials in a column by a specified time interval. |

The simplest solution would be to assign one battalion to each aircraft serial. This would be taking the chance that the artillery might land at some distance from the others, depriving the infantry of artillery support and possibly losing the artillery altogether. The alternative would be to create four self-sufficient teams of infantry, artillery, and engineers but this would confuse the command structure and degrade the capability of the artillery for massed fires, its most valuable asset. Graves finally decided to keep the artillery intact as far as possible.

With this decision out of the way, allocation of aircraft and missions was relatively simple. The 2nd Battalion would go in first in Serial 6 from Ombrone, capture La Motte, and seize high ground in the northwest. The 3rd would follow in Serial 7 from Orbetello to seize ground to the west; next would be the 460th (less one Battery) in Serial 8 from Montalto. Last would be the 1st Battalion in Serial 9 from Canino to seize ground to the south. One Battery of the 460th would be attached to the 1st Battalion for the drop. The Engineer Company (less a platoon attached to the 509th) and Regimental Headquarters and Service elements would be split between Serials 6 and 7.

Allocation of aircraft by battalions to the companies and batteries followed. At each level command was decentralized. Plane loads were made as self-sufficient as possible. In a rifle company, for example, the Commander, Executive officer, and First Sergeant would be in different planes. All plane loads would include some riflemen, a machine gun or mortar, a bazooka or grenade launcher, and if possible, a radio.

The senior man in each plane load ("stick") would be jumpmaster and the next senior "pushmaster". Men with extra-heavy loads were placed well forward in the sticks so that they could get out of the door more easily; very reliable men were put in the number three or four position to give them access to the pararack bundle release, Hopefully, the bundles would come down somewhere near the center of the stick landing pattern.

Last -- and most important -- were the individual loads to be carried by each man. These were staggering. Airborne troops could be moved as far and as fast as planes . could fly, but once on the ground they had the mobility of Caesar's legions or less, since the Romans had animal transport. Everything needed to fight and survive for several days had to go on the backs of the troopers. The average man carried 30 pounds of personal gear his weapon and ammunition, three grenades, two days' rations, water, gas mask, entrenching tool, and the like. Another 20 to 30 pounds was added in "organizational" equipment radios, ammunition for crew-served weapons, mines, explosives--the list is endless. On top of all this had to go the main and reserve parachutes and the inflatable "Mae West" life preserver .

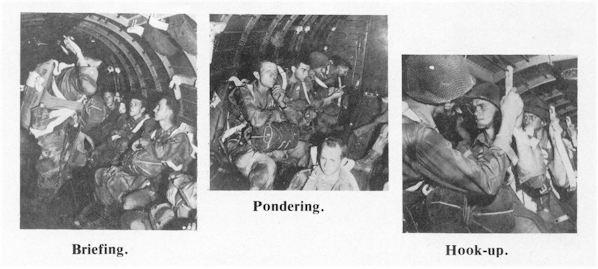

The next step was briefing. Battalion commanders briefed company commanders, who in turn briefed their officers and men without revealing the date and place of the operation. Troop briefings were with the aid of a six-foot square terrain model at the Regimental CP on which every field, road, stream, and house had been reproduced in meticulous detail. Towns and other landmarks were tagged with American place-names such as "Milwaukee" and "Hoboken".

A team of Engineers was detailed to camouflage clothing and equipment. The troopers filed through a paint-spray line* wearing and carrying the clothing, weapons, and equipment with which they would jump, and emerged in shades of yellow, green, and black. The clothing and gear were set aside and small American "invasion" flags were sewn on the sleeves of jump jackets.

| * This was ordinary oil paint, which dried hard making clothing hot and uncomfortable; worse, a man hit by a projectile was liable to have the paint (including lead) carried into his bloodstream. |

On August 6th a "skeleton" flight rehearsal was held which approximated the flight to the target area in France. The Combat Team and Battalion commanders, S-2s and S-3s, and most Company commanders went along. Although beneficial for the air-crews it meant little more than lost sleep for the airborne officers.

In early August the 442nd Antitank Company and Company D, 83rd Chemical Battalion, finished glider training and reported in to the bivouac area. On August 9th an RCT exercise which included these attachments was held on terrain chosen to match the objective area as closely as possible. Units were scattered out over fields by trucks to simulate a parachute landing; then they assembled, made reports, and went through

the motions of seizing ground. While this was pretty tame stuff for the 5l7th, which had made several large-scale jumps before leaving the States, it was badly needed by Task Force Headquarters. which had only this opportunity for practice before the real thing. *

The Combat Team was sealed off on August l0th.** Movement in and out of the bivouac area was banned, and no further contact with military or civilian personnel was allowed. Over the next two days units organized into Serials and moved to their departure airfields. The Combat Team CP opened at Ombrone on August 13th.

Most of the departure airfields were dusty cow-pastures with aircraft parked along dirt runways. The troopers set up camps and began another period of waiting. Final briefing was completed. Although the majority had long since guessed that their destination was France, for the first time it was officially confirmed. English-French phrase books appeared containing such handy phrases as "I am wounded," and "Where is the enemy?"

| * Time and parachute limitations precluded a live

jump exercise.

** On this date the CINC Mediterranean received the final go-ahead for DRAGOON. Fortunately, no inkling of the high-level indecision ever reached the troops. |

Maps, 'escape kits' and invasion scrip were issued. To be on the safe side most officers took maps covering huge areas from Spain to Switzerland, adding many pounds to their existing overloads. The more fortunate enlisted men were given mimeographed sketches. The escape kits, issued one per ten men, were small packets containing maps, tiny files, and compasses. Basically intended for shot-down aircrews, they were highly, prized because they also contained a hundred dollars in cash .

During the last hours of daylight on the 14th equipment bundles were packed, rigged, and dropped off beside each plane. Mess tents remained open after the evening meal and much coffee was consumed. USO troupes performed, movies were shown, and little tubes of grease paint (made by Lily Dache, manufacturer of women's makeup) were distributed. Much entertainment was derived from painting hands and faces like Indians going on the warpath.

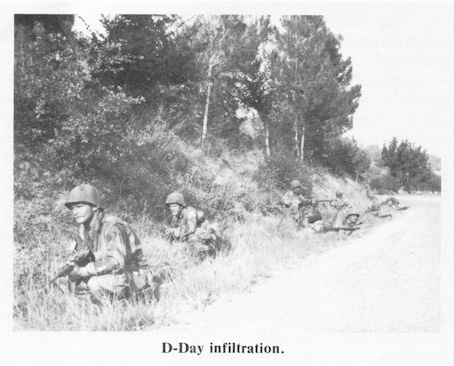

At around midnight the paratroopers formed by sticks and marched to their planes. After slinging the pararack bundles they fitted parachutes, adjusted weapons and equipment, and climbed aboard.

Colonel Graves reflected with amusement on a letter he had received just before leaving Frascati. It was from the Commanding General of the Rome Area Base Command, directing him to report to that headquarters at 1400, August 15th, to explain why so many vehicles with other unit markings were in the 517th area. At least that was one chewing-out he wasn't going to get.

Chapter III

Dragoon

D-Day

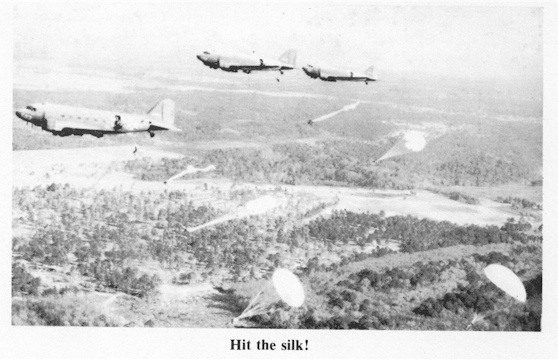

It was a sight that had rarely been seen before and which may never be seen again.* An hour after midnight on 14/15 August three hundred ninety-six C-47 aircraft, scattered over a hundred and fifty miles at ten airfields in west-central Italy, began turning over their engines. At ten-second intervals planes taxied down dirt runways, lifted off, and circled into formation. The dust, compounded by darkness, was so thick that many pilots had to use compass bearings to find their way down the runways. Takeoff times were from 0136 to 0151 for the ten serials, depending on the distance to the first check point at Elba. Each serial required over an hour to get into formation, a column of "V of V's" nine planes wide. The entire formation, from the head of the first serial to the tail of the last, was over one hundred miles long. This was the ALBATROSS mission, to drop 5,630 paratroopers in Southern France.

| * It was the last large-scale night jump of World War II. |

It was one hundred and eighty miles to Agay, the Initial Point on the French coast. Serials spaced five minutes apart cruised at 2,000 feet at 140 miles per hour, with individual planes 100 feet apart. The weather forecast was favorable; ground haze and 6-mile winds were expected over the Drop Zones . Radio beacons would guide the serials from Elba to the northern tip of Corsica. From there, radar and Navy beacon ships would lead them to Agay, where each serial would descend to 1500 feet *, slow to 125 miles per hour, and home in on its drop zone by beacons and lights to be put out by Pathfinder Teams.

Each plane carried six equipment bundles in pararacks beneath its belly. More bundles were in each plane, and men overloaded with equipment sweated it out under the special tension known only to paratroopers. Extra fuel was carried in 50-gallon drums within each plane because of the distance to be flown, and for the same reason sticks averaged only 16 men. All were relieved that at last the preparation and waiting were over and the time for action had arrived.

| 517th units were under the impression that jump altitude was to be 700 feet, and attributed jumping at higher altitudes to the need for climbing above the fog; but a 1500-foot jump altitude had been planned from the start. |

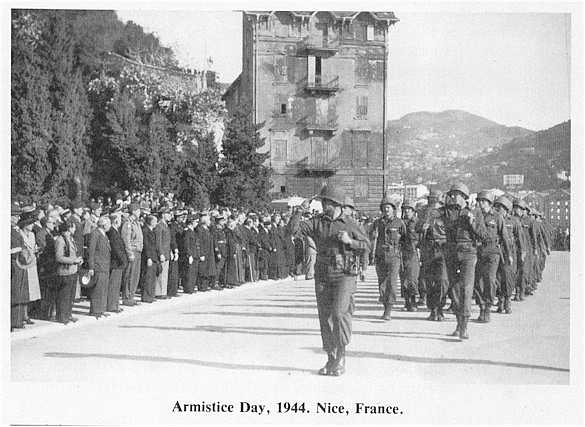

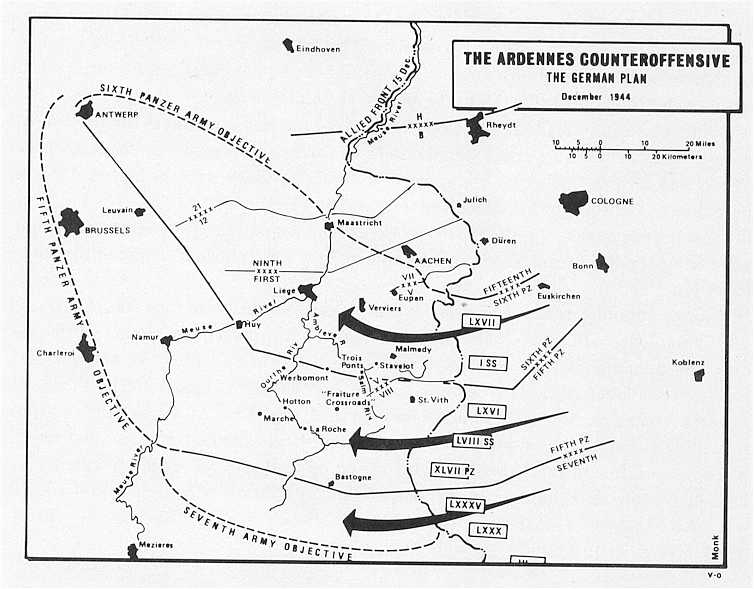

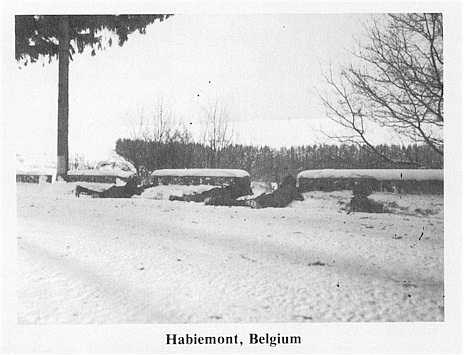

Nine Pathfinder planes, each carrying a team of ten men, preceded the assault serials by an hour. Three teams were to drop on each DZ beginning with the 509th team on DZ C. The Pathfinder mission was under the same guidance as the main assault, but after landfall at Agay each element and plane would rely entirely upon the navigational skills of pilots and crews.